Rolf Hochhuth (1931-2020)

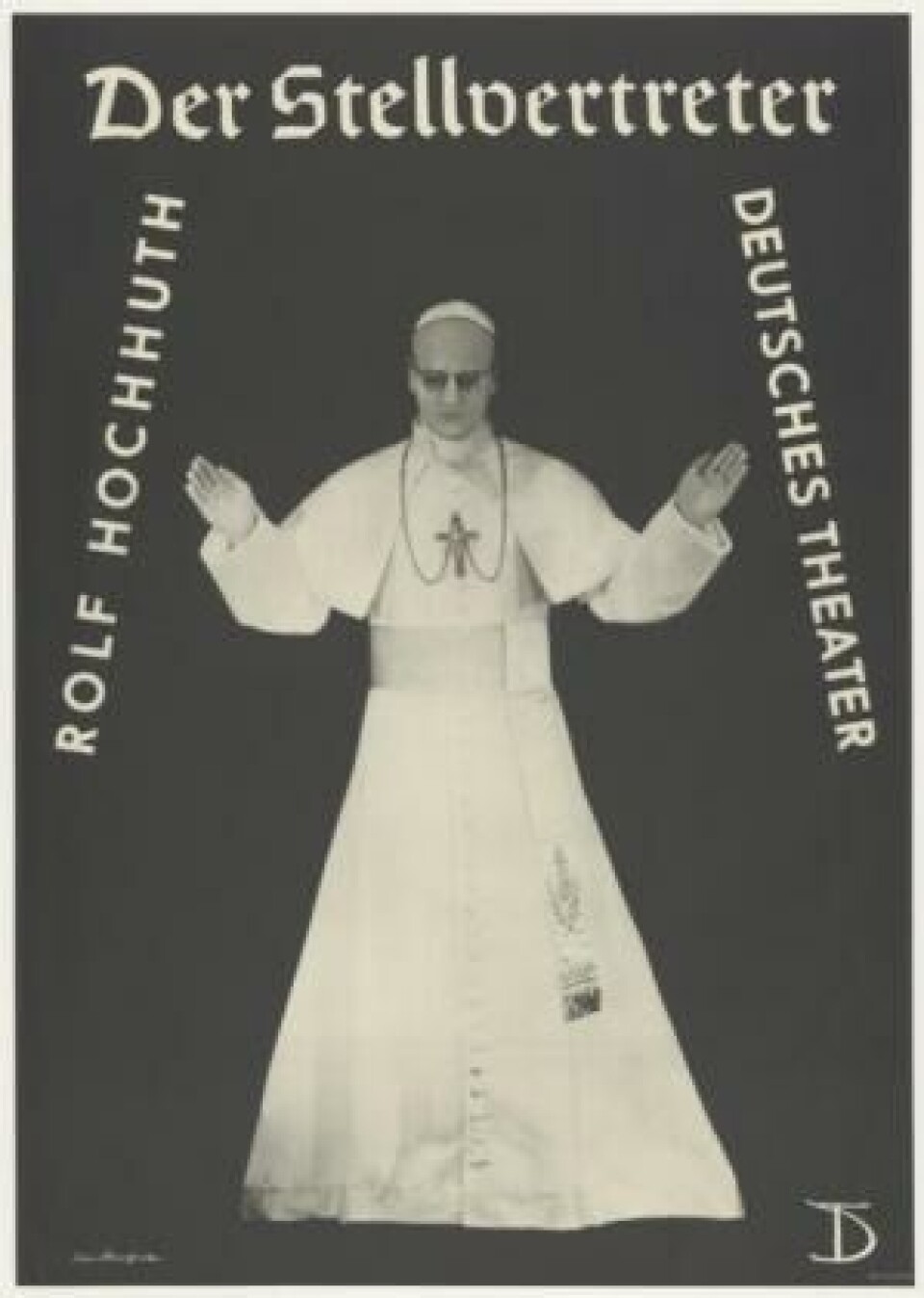

With Hochhuth’s play The Deputy (Der Stellvertreter) as a spearhead, the German post-war theatre re-entered politics and challenged historical memory.

In 1959 Rolf Hochhuth, a young editor working for the Bertelsmann book club, went to Rome to research the diplomacy of the Vatican during WW II and, more precisely, the role of Pope Pius XII during the Holocaust. The play he extracted and composed from this material had the title The Deputy (German: Der Stellvertreter, ed. rem.), referring to the deputy of God on earth, and addressed the scandalous reluctance of the Vatican to protest the deportation of Jews into extermination camps. The text of The Deputy consisted not only of the play with fictitious characters based on real people and their dialogues but also included documents that would prove the historical issue at stake. That is one important element for what critics and scholars later defined as ‘documentary theater’ while Hochhuth has always preferred to call this ‘political theater’.

World Premiere by Piscator

The political dynamite of The Deputy remained sealed for a couple of years as nobody wanted to touch this issue in West Germany until the play was offered to Erwin Piscator. The returned emigrant was known as one of the most productive innovators of theatre in the 1920s, where he collaborated with Brecht on the development of epic theatre and introduced the use of film on stage at Berlin’s Volksbühne. Piscator enthusiastically welcomed the young playwright and staged The Deputy in 1963 at Freie Volksbühne in Berlin (still residing in an old theatre at Kurfürstendamm). The world premiere received a lot of attention leading to protests against Hochhuth and the theatre while the book edition became a bestseller. The seemingly sacrilegious subject was attacked by conservatives and Catholics despite the historical evidence that came to light with it. Almost all subsequent international productions around the world, Peter Brook’s 1963 Paris staging among them, were confronted by furious protesters and accompanied by heated debates. With Hochhuth’s play as a spearhead, post-war theatre re-entered politics and challenged historical memory. In Germany it coincided with the start of the Auschwitz trials in Frankfurt about which Peter Weiss wrote his play The Investigation from eyewitness reports, setting the second milestone of the ground-breaking documentary theatre researched and assembled by a new type of playwright with political commitment.

The Filbinger case

The combination of politics and literature that reveals scandalous affairs remained the principal characteristic of Hochhuth’s work. In Soldiers (1967), the second play after his break-through, he questioned Winston Churchill’s fire-bombing strategies against Nazi Germany; in Lysistrata and the NATO (1974) he dealt with American military politics in Europe; and war and politics were even looming behind the monologue drama about Ernest Hemingway’s suicide, Death of a Hunter (1976). When Hochhuth published Eine Liebe in Deutschland (A Love in Germany) in 1978, this novella revealed the past of Hans Filbinger, prime minister of Baden Württemberg, as a Nazi military judge who sentenced soldiers to death even after the end of the war and before he made a brilliant career in West Germany. Filbinger was forced to resign from office. In the subsequent play Juristen (Lawyers) Hochhuth addressed the Filbinger case again in order to investigate the historical pattern behind it.

Wessis in Weimar

By the end of the 1970s the wave of documentary theatre had vanished as theatre also became less politicized. The playwright remained the expert for disclosure dynamite, now dealing with the issues of pharmaceutical research among others. Only after the German reunification he would find again a subject of historical dimensions in the dealings of the West German Treuhand trust selling and dissolving East Germany which is described in scenes of criminal acts and their consequences. But Wessis in Weimar (1993) became also spectacular through its controversial staging by Einar Schleef at Berliner Ensemble, who was reducing the text for powerful chorus arrangements rather than presenting the play in the style of Hochhuth’s quasi-naturalistic realism. In this case Hochhuth was the protester, who, as a surprise business, bought the real estate of Berliner Ensemble to demand from future artistic directors the staging of his Deputy and a theatre of playwrights according to his understanding.

Hochhuth explained his poetics of historical research in his comprehensive lectures The Birth of Tragedy from War (2001), a book that seems nearly forgotten but all the more important also for what documentary theatre became after Hochhuth’s heyday. Creators of contemporary documentary theatre like Rimini Protokoll, Milo Rau and, most of all, Hans Werner Kroesinger owe, despite all differences, much to the tradition coming from Hochhuth, the theatrical researcher with political alertness.

Rolf Hochhuth died 13 May 2020, age 89, in Berlin. (Published 05.15.2020)