Propaganda-Art, Trial-Theatre and Amazon Anger

The Coronavirus pandemic has made obvious that the state can and should control the market by means of strong institutions. In propaganda-art, many of these institutions have already been established. But society has to follow. Everything else is a scandal.

Propaganda-art should make the spectators see that society doesn’t have to be as it is, that the status quo is unacceptable and then it must inspire the audience to develop a new consensus. These three steps are the essence of the genre, according to theatre maker Milo Rau in his 2019 published lectures The Historical Feeling. Why should we be interested in propaganda-art today? Despite its reputation, destroyed by lying demagogues like Goebbels, Stalin and co., it can encourage the creations of more equal societies. This is exactly what we, Blaue & Poppy, want to achieve in our performance-tryptic The Personal Encounter with World Politics. We have already done two performances: The Criminal Complaint and The Interim Report; and I claim, they both classify as propaganda-art. I want to find out if this is true while consciously utilizing this manual for purposes of staging our last performance: The Trial Against Ourselves. Our own strategies might also supplement Rau’s ideas.

In our performance-tryptic, we try to criticize and suggest alternatives to contemporary global capitalism. It therefore seems appropriate for this essay to also discuss economic theory about equality and its propositions. This is both an artistic inspiration and a more scholarly foundation of our propaganda-art. In the beginning of the pandemic, one often heard that when confronted with the Coronavirus everybody is equal. The opposite is the case. Economically privileged people are of course less exposed. In order to problematize economic inequality between people I will reflect on the unequal effect the virus has on people in societies.

Milo Rau illustrates the three steps of propaganda-art by referring to his own political performance project City of Change (2011). First, he and his theatre company, International Institute for Political Murder deconstructed the idea that the Canton of St. Gallen is democratic. As in many other European cities, a big part of the tax paying population, namely foreigners, are not allowed to vote. Rau and his company made this “normality” appear as contingent and changeable by suggesting to either quit calling Switzerland a democracy or to give foreigners voting rights. Second, they founded the institution Government of Change, including a Propaganda-Department and a Government Agency of Theory. The “propaganda” formulated within these imaginary institutions, led many to discover the highlighted problem and the formerly accepted legislation suddenly seemed unacceptable. This resulted in a majority supporting voting rights for foreign citizens and thus, third, a new consensus visible in polls of local newspapers, appeared.

First step: society becomes visible as a result of (in)human history

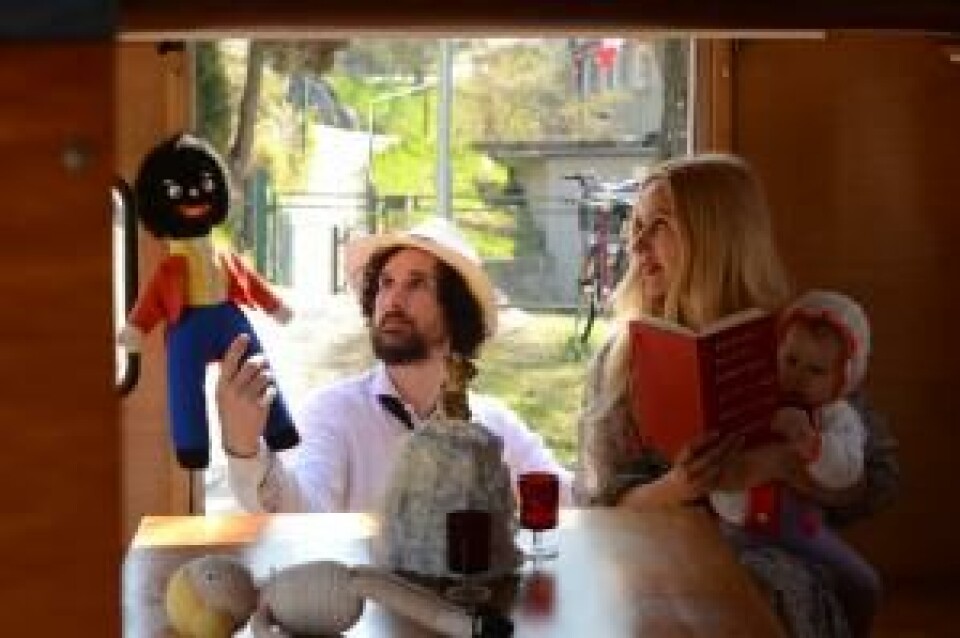

Christmas Eve, 2015 in Rio de Janeiro we, Blaue & Poppy and our baby boy Béla, got assaulted by two armed men from a favela. We believed the narrative of society, “we are the innocent victims; they are the perpetrators” and pressed charges against the two men at the Rio tourist-police-office and they were caught. Later we began to reflect and ask ourselves: isn’t poverty, caused by unequal distribution of common global goods, the reason for this assault? Aren’t we part of the global middle classes that exploit the global underclasses? Aren’t we therefore, to a certain extent, also responsible for this unjust distribution?

As if she were our prosecutor, Indigenous actress and activist from the Amazon Kay Sara is bringing attention to the question of guilt in Brazil. She is the main character of Milo Rau’s Antigone in the Amazon which would have premiered in April 2020, but has been postponed to April 2021 due to the pandemic. That’s maybe why Kay Sara performed her opening speech of the Wiener Festwochen in May 2020 with a mixed identity — partly being herself, partly Antigone. “This Madness Must Stop”, co-written with Milo Rau, was video-transmitted from the Amazon directly into our living rooms. In Sophocles’ tragedy, Antigone criticizes Creon who is coming to power after a war and who is trying to make his country great again with big symbolic gestures. He forbids the burial of Antigone’s brother, a so called traitor to the nation. If Kay Sara is Antigone, the Creons are the Brazilian right-wing politicians, the Westerners, the white, the middle- and upper-classes. She warns them: “If you listen to yourself, you will find only your guilty conscience.”

It is as if she also talks to us, Blaue & Poppy. We didn’t fully understand our shameful position in global capitalism, the abnormal in the normal, until we were confronted with the assaulter’s knife. In The Criminal Complaint performed at Sørlandet’s Art Museum in 2018 we told the audience about this awakening. We transformed the Rio-experience into propaganda-art, as I would label it today. Proclaiming that the poverty of the armed men from the favela is a result of our own structural violence[1], we were taking the first step in propaganda art. We thus showed, hopefully, that inequality is a human creation, which can and should be altered and challenged. We found our guilty conscience, but not only by listening to ourselves — first we had to be assaulted in Brazil. With the knife before our eyes, we began to understand.

In The Interim Report, performed a few months later at the prestigious Rio Art Museum, among other venues, we made a calculation. Here we investigated the “truth,” of us being the victims and they the perpetrators, by looking at the effects we had on each other’s lives before, during and after the assault. Our first reckoning was about the time before the assault and the fact that we had watched the Brazil World Cup 2014 on Norwegian national TV. The sport event had devastating effects on the very poor of Rio, and by extension, for the two men from the favela who assaulted us. During our investigative journey, even the police defined poverty as the reason for their violent attempt to rob us. We learned from the police and later from a study by social geographer Phyllis Bußler[2], that favela houses were removed to create new infrastructure, and social programs were cancelled for the financing of the mega event. We caused harm in the men’s lives prior to our “encounter” by way of supporting the World Cup; yet, they had caused none in our lives before the assault. The second account included the incident on Christmas Eve 2015 wherein the two armed men caused the most harm, inflicting near-death trauma on us. The third account was the consequences of the assault. We pressed charges against the two men, and that is why one of them was imprisoned; while the other one was underage and got custody for young offenders. We became traumatized following the incident on Christmas Eve 2015, but the artistic work was healing for us. Not only did the performances have therapeutic effects, they were also a legitimate career boost. On the basis of the assault we began this successful performance-tryptic, so in a way, we have our assaulters to thank for the success. The result of the calculation was this: we, Blaue & Poppy, had inflicted more harm in the lives of the men from the favela than they had in ours. They even helped us in benefitting from economic and cultural capital. Turning the guilt-question on its head, it became even more obvious that everything in society in principle could be completely different. In this way we deepened the first step of propaganda-art in our project.

Sophocles’ Antigone didn’t follow Creon’s prohibition of burying her brother, she interred him, following the moral law: every dead person must be buried. Also the two men from the favela acted, consciously or not, according to an other law outside official rule. They followed a universal right to food, shelter, clothing, if one presumes that they wanted our money in order to pay for one of these necessary items or obligations. At the same time, they broke official Brazilian laws against armed property crimes (the violent incident can also be seen as a break of a universal moral law). Is it really possible to compare burying a brother out of compassion and violently assaulting middleclass tourists? I think it is possible if one takes in to account that the ruling capitalist order might prove deadly for the two men. Can one say that the knife-threat was an attempt to turn a global power hierarchy — in which we are normally in the middle when they are at the bottom — upside down? In the moment of the assault this hierarchy was temporarily reversed. But they were caught, and the old hierarchy was back at work again. Like the burial Antigone carried out, the assault has mostly a symbolic effect: thematising it in our performance-tryptic adds a subversive artistic dimension. The men’s knife didn’t only return to us like a boomerang, it flew all the way to our performance audience (and now also to you as a reader). Hopefully it has also made them (and you?) aware that the official narrative concerning guilt and poverty is a changeable construction. Are there also specific economic arguments for the claim that inequality is contingent and should be altered?

In his new book Capital and Ideology, published in spring 2020, Thomas Piketty argues that change is possible. He presents unseen historical material from Scandinavia. While Swedes enjoy a high level of equality today, just about a hundred years ago inequality, and its ideological defense, dominated in Sweden. In the late 19th century, for instance, the official policy deemed that political clout depended on the amount of property a voter owned. Sweden currently stands out as a paradise of equality due to an almost uninterrupted social democratic governance from 1932 to 2006. This development shows that an essentially equal society of people does not exist, which many believe Sweden and Scandinavia to be. Societies can always be changed, a premise for all propaganda-art, especially for our performance-tryptic. Brazil for instance, which many think is a fundamentally unequal country, could become egalitarian by establishing socially just institutions.

In our present time, this becomes particularly obvious. The pandemic reveals that taming capitalism is a realistic option. The seemingly impossible, governments controlling the market, became possible within a matter of days. The lockdown of the capitalist machine in the spring of 2020, as well as increased social welfare policies in some countries, shows that societies can radically and quickly change if the political will exists, making propaganda-art extra meaningful to perform.In his historical example Piketty focuses on the nation state. All artistic performances I am discussing have an international dimension. In the book’s more visionary section, the author provides almost a manual for propaganda-art utopias that are critical of global capitalism. Piketty explains: the market of today, acting internationally, has to be controlled by globally established institutions, including laws. Considering that we, Blaue & Poppy, by simply enjoying the Brazil World Cup on TV in Norway, have produced some difficulties for the two men in Rio’s favela neighborhood, makes the following evident: problems that are created globally need to be solved globally — that is, not only in the regions where they have negative effects. We attempt to provide an artistic example of this by accusing ourselves for something we did in Europe, namely the consumption of the World Cup on TV, an event that continues to have negative effects on the other side of the planet, in Brazil.

This is also the precondition for Milo Rau’s other propaganda-art performance from 2015, The Congo Tribunal (streamed at the Berlin Schaubühne in June 2020). He staged his tribunal-performance in Eastern Congo and Berlin, dealing with exemplary crimes committed during the civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo since 1996. The African state lacked a functioning juridical system that could sentence local war actors, and the world had no legal way of punishing crimes committed on a global scale by multinational companies. Rau and his expert team “created” a jurisdiction combining local, human and financial rights. This action made many see the possibility of legal changes in their country. Already in the preparation phase people strongly supported the tribunal-performance.

Second Step: compared to a utopic institution the accepted becomes unacceptable

The long accepted legal situation in Eastern Congo made an official tribunal impossible. Confronted with Milo Rau’s artistic plans, the situation became unacceptable for many. Rau worked with Jean-Louis Gilissen, a counsel at the international criminal court as chief judge, and the Congolese lawyer Sylvestre Bisimwa as chief investigator. Local witnesses and complainants participated and even the accused showed up — warlords, Congolese politicians, and also representatives of international companies who mine coltan at the expense of the local population.

Nobel prize winner in Economic Sciences (2001) Joseph Stiglitz has long focused on these issues. His 2002 bestselling book Globalization and Its Discontents was re-published in 2017 because of increased relevance. In it, he criticizes the acknowledged globalization strategy among many politicians and economists in the neoliberal world following the Reagan-Thatcher-era. But what is Stiglitz’ argument for not accepting the accepted within economy? Can his reasoning be supportive when taking the second propaganda-artistic step, since that step is exactly about presenting the established status quo as unacceptable?

Since the 1980s Reagan-Thatcher-era the Washington Consensus has predominated global economics. In a 2000 interview from the journal The Progressive, Stiglitz describes this trend as a “a set of policies formulated between 15th and 19th streets by the International Monetary Fond, U.S. Treasury, and World Bank,” bringing attention to the irony that a small elite in Washington defines the economical world order.These policies promote liberalized international markets with almost no rules for global corporations that profit off of consumers, cheap labor and local infrastructure around the world (and eventually from warlike situations like the one Rau thematizes in Eastern Congo). In order to defend the neoliberal doctrine socially, it was labelled a “trickle-down economy.” The “trickle-down” logic assumes that if the richest have the best conditions for producing wealth, this will in turn benefit everybody, trickling down even to the underclasses. According to Stiglitz this model has failed.

FIFA, organizing the World Cup, is such a company. Stiglitz validates our performance-arguments, wherein we implicate ourselves in our enjoyment of the World Cup in Brazil on TV. The discontent of globalization is due to a construction error: international business laws have made it easy for global players to act worldwide. As part of the middle classes, we are profiting from this error when we consume, as we, Blaue & Poppy, “verified” during The Interim Report calculation performance. The destruction of favelas and social programs in Rio, a breeding ground for property crime, seems to be an effect of the neoliberal politics Stiglitz criticizes. Minimizing rules for international companies, may in some cases create jobs. But often workers, especially in developing and newly industrialized countries like Brazil, can hardly make a living from their wages and have only few and insufficient rights. Companies should provide work without committing structural violence. A leading question in our performance-tryptic is: can this precarious situation in and of itself be a good reason for the very poor to rob those in the middle and upper classes?

Kay Sara accuses privileged people, like ourselves, Blaue & Poppy, for exploiting the underprivileged in Brazil. Sophocles’ Antigone accuses King Creon not only for acting wrongly but also for knowing it, and then doing it anyway. Kay Sara accuses the Creons of today for immoral behaviour — for instance, president Jair Bolsonaro whose politics led not only to himself and his family being infected with Coronavirus, but also to scandalously high Covid-19 death-rates in Brazil (making it impossible to bury all the corpses of the underprivileged, a bizarre similarity to Sophocles’ tragedy). Kay Sara also accuses the Creons from the educated middle and upper classes for listening to critical speeches like her own, applauding to them even, but not changing the criticized behaviour. We, Blaue & Poppy, are also a target for this double critique. We are listening to Kay Sara’s accusations. We know that we are acting unjust. We even formulate an artistic self-accusation. And we continue to act wrongly. But we, in opposition to Creon, want to stop it before it is too late. We need the structures to help us. We need an official law against structural violence that forces us to do right. This is also the reason why we don’t follow the advice Kay Sara gives: shutting up and instead giving voice and agency, the stage, to the underprivileged alone (which is not characteristic of her speech-performance either, largely directed and written by privileged artist Milo Rau). We, Blaue & Poppy, prefer to criticize our unjust behaviour in propaganda-art instead of ignoring it. We are one part of the problem, and we should also contribute to solving it, by means of the three steps.

According to Milo Rau one can take the second step of propaganda-art by manifesting Imaginary Institutions. Through the lens of a utopian institution a fairer society becomes visible. The idea is, when such an artistic pre-enactment of a better world is compared to the unjust present, people may reject that which was formerly accepted. What once was the norm, looks disgraceful in comparison to a better alternative.

In his 2006 book Making Globalization Work Stiglitz imagines institutions theoretically: any country where a given corporation is profiting “should provide a venue,” in other words a juridical institution, “in which lawsuits” against this foreign corporation “can be brought in” since international corporations should be held “accountable for [their] action in other jurisdictions”. Obviously not only from a propaganda-artist point of view does it makes sense to manifest imaginary institutions. It also applies when trying to react to important social demands in the contemporary global economic order. According to Stiglitz, laws and strong state institutions which protect the poor, are appropriate remedies against an unregulated deadly capitalism.

The economist’s daydream of venues like this one is a fantastic prelude to their specific and concrete manifestation in the art field. And the artistic pre-enactments can be forerunners to official venues in the political field. For example, after Rau’s tribunal-performance many Congolese no longer accept the formerly accepted lack of a juridical system that would make it possible to punish war crimes. It did not stop there: now an official tribunal is under development, having Rau’s artistic tribunal as a model. So, performances can change society to a better and more just one — an encouraging and motivating fact for any propaganda-artist.

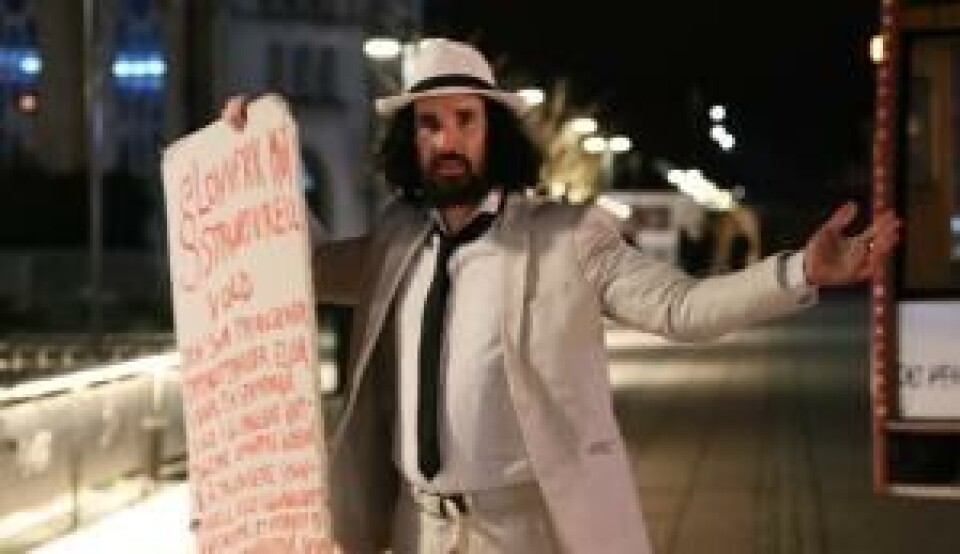

A law against structural violence would be an appropriate legal institution to combat poverty, and the unjust distribution of common global goods. International companies and their customers profit often alongside unjust structures. Many of the acts this law would prohibit are global crimes, as shown in our example of the FIFA World Cup. So, idealistically it would even be internationally enacted. But the opposite is the case: it isn’t enacted in one single state of the world. This is unacceptable from a universal moral point of view. But also constitutionally, since democracies claim to legally protect citizens against all types of violence that is produced by humans. In our Criminal Complaint performance we, Blaue & Poppy “enacted a law against structural violence”. Then we “pressed charges against ourselves” for having “broken the law” in Rio. We installed a “criminal complaints office” in our fire engine and succeeded in taking the second step of propaganda-art, inspiring our audience to stop accepting the formerly accepted through imaginary institutionalizing. Some spectators “pressed charges” against themselves for having broken our law against structural violence. I interpret this as a recognition of the law, and implicitly as a rejection of a society without such jurisdiction, which the spectators until then obviously tolerated.

Third step: a new consensus appears, demanding change

The Washington Consensus has not been totally abandoned. The World Trade Organization (WTO) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) continue to act according to neoliberal rules. But it seems that many are on the way towards a new consensus, especially now in the time of Covid-19. The pandemic shows that societies, like Germany, where public health care wasn’t minimized much, are in less danger of collapsing than those that have massively privatized it, like in the U.S. and Brazil. Nations that maintain strong social security nets, such as Norway, manage to save more people experiencing economic catastrophes, like not being able to work due to quarantine and lockdown. Can self-interested actions of corporations really have unintended social benefits, as the theory of the invisible hand of the market solving all social-economic problems, is promising? According to Stiglitz this famous hand might be invisible simply because it doesn’t exist. He seems to be right. At least it was hard to notice any positive effect from the market’s invisible hand in, for instance, the favelas during lockdown. (Do we, Blaue & Poppy, have to go as far as accusing ourselves for profiting from structures that assist the Coronavirus pandemic spreading in Rocinha, the favela in Rio where our assaulters live, and where social distancing and routine hand washing is next to impossible? It sounds exaggerated. But there is some rationality in it, as for instance, privileged countries in Europe have bought up test material — and now also vaccination-concepts — from the international market, thus saving European citizens, sometimes on the expense of the ones from less privileged countries like Brazil.)

The positive experiences of governmental market regulation in spring 2020, in combination with relevant welfare policies, is one more argument for aspiring to develop a consensus around enacting a law against structural violence. Did we, Blaue & Poppy, take the third step of propaganda art? I’d say, we haven’t really been able to inspire the creation of a new consensus, defined as a long-term insight in a big or small group. The rejection of the juridical status quo by spectators “pressing charges against themselves in the criminal complaint office” has hardly become a consensus, demanding to enact the law.

Milo Rau’s Congo Tribunal performance ended with a “verdict” against the Congolese Government and the multinational raw material conglomerates. Another part of the tribunal, staged in Berlin, ended with a second “verdict”, holding the World Bank and the EU responsible for the crimes in Eastern Congo. Even if these artistic judgments weren’t officially valid, a minister of mining in the South Kivu Province of Congo was suspended as a result of Rau’s performance. Such factual consequences and the big acceptance of Rau’s imaginary institution made it obvious that he had managed to create a consensus among many people regarding the creation of an official tribunal in Eastern Congo.

A consensus among the majority of a given society, wanting an official law against structural violence, would imply a majority voting for politicians with the same values, who then finally would enact the law. If this would happen internationally or in a country where we create our art, we’d be able to have an official trial against ourselves, where we’d be accused for acting out structural violence. But for now that’s only a daydream (demanding to be real). We are in a very different situation than Milo Rau. He staged a tribunal, because crimes, obvious for most people, where committed, but no legal system existed, that can deal with those crimes. We had to suffer a crime ourselves, an assault, before we were able to see the structural crime, we think we have committed against our perpetrators. This is a reversed crime story, and some would call it masochism. The problem is not as obvious as the crimes committed in the Congolese civil war. We want to make visible the invisible and unjust structures which we believe are criminal. At the same time, we state that every privileged person commits structural violence. To achieve unanimity, i.e., a consensus, around the importance of enacting a law against structural violence in a society where most people are guilty, would be difficult even for populist politicians, let alone the propaganda-artists. Nevertheless it is mandatory.

We, Blaue & Poppy, try to create a precedence. We are convinced of our guilt. But a judge and jury have to decide

independently if our claim is true. Their verdict should not only be based on our and the prosecutor’s arguments, but should also consider the pleadings of a defense attorney, against our will arguing for our innocence. She could underline that the connection between our acts and the suffering of “the two criminals from the favela” can’t be depicted concretely and that in reality, we are helping the underprivileged, including the two men, by creating art that is critical of capitalism. In any case, this trial will be a staged one, since it cannot take place in an official court. In addition, we are hiring the judge, defense attorney and prosecutor ourselves and will pay them with a cultural budget. Not because we want it to be like this, but due to the political realities that make it impossible to go about things in the official, legal way. The absence of a general consensus that would lead to a democratic law-enactment, and subsequently to an official trial implies, The Trial Against Ourselves is staged fiction. Court-theatre.

“I’m not speaking to you as an actress,” Kay Sara states to the world wide theatre audience in the sofa-auditorium in front of the Covid-19 safe laptop-stage. “It’s no longer about theatre.” The Indigenous of Brazil, being less resilient than us, are threatened by the danger of Coronavirus infections, exploitation of precious metals and deforestation. Brazil’s favela-inhabitants, lacking sufficient hygiene-infrastructure, are not less threatened by the danger of infection, work exploitation and house demolishing. Both Kay Sara’s and our attempts are two sides of the same coin, even if the guilt question is incomparable. She talks critically as a potential victim; we talk self-critically as potential perpetrators. The common ground is the want for structural violence to end. We both think the situation is too serious to play theatre. But paradoxically this is exactly what forces us, Blaue & Poppy, into doing theatre. Lawlessness has become law. The lack of consensus around enacting a law against structural violence is scandalous when it comes to the situation in the Amazon rainforest and the favelas, among other places. In The Trial Against Ourselves we, Blaue & Poppy, can only act as if the law were enacted. To act as if, means to be an actor. We cannot officially go to court against ourselves, only fictively. We don’t know the outcome of this trial, as it depends on the actor who plays the judge and on the jury, consisting of spectators. Also here: theatre terms. Even if professional jurists would do the job, the non-official context would make them become actors, not being able to enforce a real verdict. In order to not hide this, actors with juridical competence will do this trial-play. “When lawlessness becomes law, resistance becomes duty,” Kay Sara quotes Thomas Jefferson. (The American president, who, although he had around 600 slaves throughout his life, formulated the American version of the human rights, officially condemning slavery. All of us critical artists and intellectuals from the exploitative classes are schizophrenic Jeffersons, as Milo Rau pointed out in a zoom-debate at Münchener Kammerspiele, April 2020). To combat violent structures, and come closer to the official enactment of a law which forbids them, the jurist-actors and ourselves, Blaue & Poppy, will protest against our own theatre acting and demand it to be a real trial. In this respect we aren’t like Creon, a theatre character who hates himself for acting cruelly without ever changing his behaviour. We are people of flesh and blood wanting to change reality but are trapped in a theatre framework. Still, we use this framework, trying to create a new consensus among the audiences, functioning as an exit from the theatre. Thus we want to perform the problematic contradictions between ideal and real jurisdiction more explicitly than Rau. He successfully stages The Congo Tribunal as realistic as possible, which in his terminology doesn’t mean to represent reality but rather that the representation in itself becomes reality. In our case the artistic category of “theatre” becomes a protest form against the lack of a law. Or, to speak in Rau’s terms, the trial that should be official and realistic, becomes theatrical in an attempt to scandalize against it not being real. In addition, we also try to solve the Jefferson-self-contradiction of being privileged critical artists and intellectuals at the expense of the underprivileged, since this is a case against ourselves.

The audience-jury will, together with the judge-actor, conclude: guilty or not guilty. If we are found guilty, they can decide if we should be punished in the parallel universe of the arts. Or if we should continue fighting for establishing a law against structural violence which one day can lead to a punishment in an official juridical reality. In any case, we, perhaps together with the prosecutor-actor, will propose that obliging us to continue this fight should be part of the verdict. The implication: we have to find spectators who stage a trial against themselves, on the basis of the law against structural violence. If we do so, and those trials against themselves also would end with a guilt-verdict, obliging new audiences to stage a trial against themselves and so on and so on, trial-conflagrations may inflame. All of them collectively demanding to be officially acknowledged trials on the basis of an officially enacted law against structural violence. In this admittedly very utopian future, we, Blaue & Poppy would, together with all the other propaganda-artists enacting a trial against themselves, possibly succeed in taking the third propaganda-artistic step: inspiring to develop a consensus according to which the structures that force us to do theatre and commit structural violence, have to be combatted by law.

This essay has been published in Norwegian, in Norsk Shakespearetidsskrift 2-3 2020, August 2020. This English text is an updated version, published 09.21.2020.

[1]Johan Galtung coined the notion “structural violence” and defined it as “avoidable impairment of fundamental human needs” (1993, p.106). Galtung underlines that it is an indirect form of violence: “there may not be any person who directly harms another person in the structure. The violence is built into the structure and shows up as unequal power and consequently as unequal life chances” (Galtung, 1969, p.171). It might seem absurd suggesting to enact a law against structural violence, holding somebody responsible for this form of indirect violence, as we do in our performance-tryptic. Isn’t it impossible to blame a person for non-personal violence? I assert that there are always individuals who concretely profit and needlessly suffer from concrete acts of structural violence. Galtung himself points out the exploitative element: “The archetypal violent structure, in my view, has exploitation as a center-piece. This simply means that some, the top dogs, get much more (here measured in needs currency) out of the interaction in the structure than others, the underdogs.” (Galtung, 1990, p. 293). (All quotes are from Galtung’s articles in the Journal of Peace Research 1969, 1990 and 1993.)

[2] Bußler, P., 2013, Project based Urban Development in Rio de Janeiro: Processes of expulsion, spatial segregation and social exclusion in the context of the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games. (PhD), Universität zu Köln. Available at: https://www.kooperation-brasilien.org/de/veranstaltungen/runder-tisch-brasilien/rtb-2013/Bussler%20-%20Projektbezogene%20Stadtentwicklung%20in%20Rio%20de%20Janeiro.pdf [Accessed 28 August 2020]