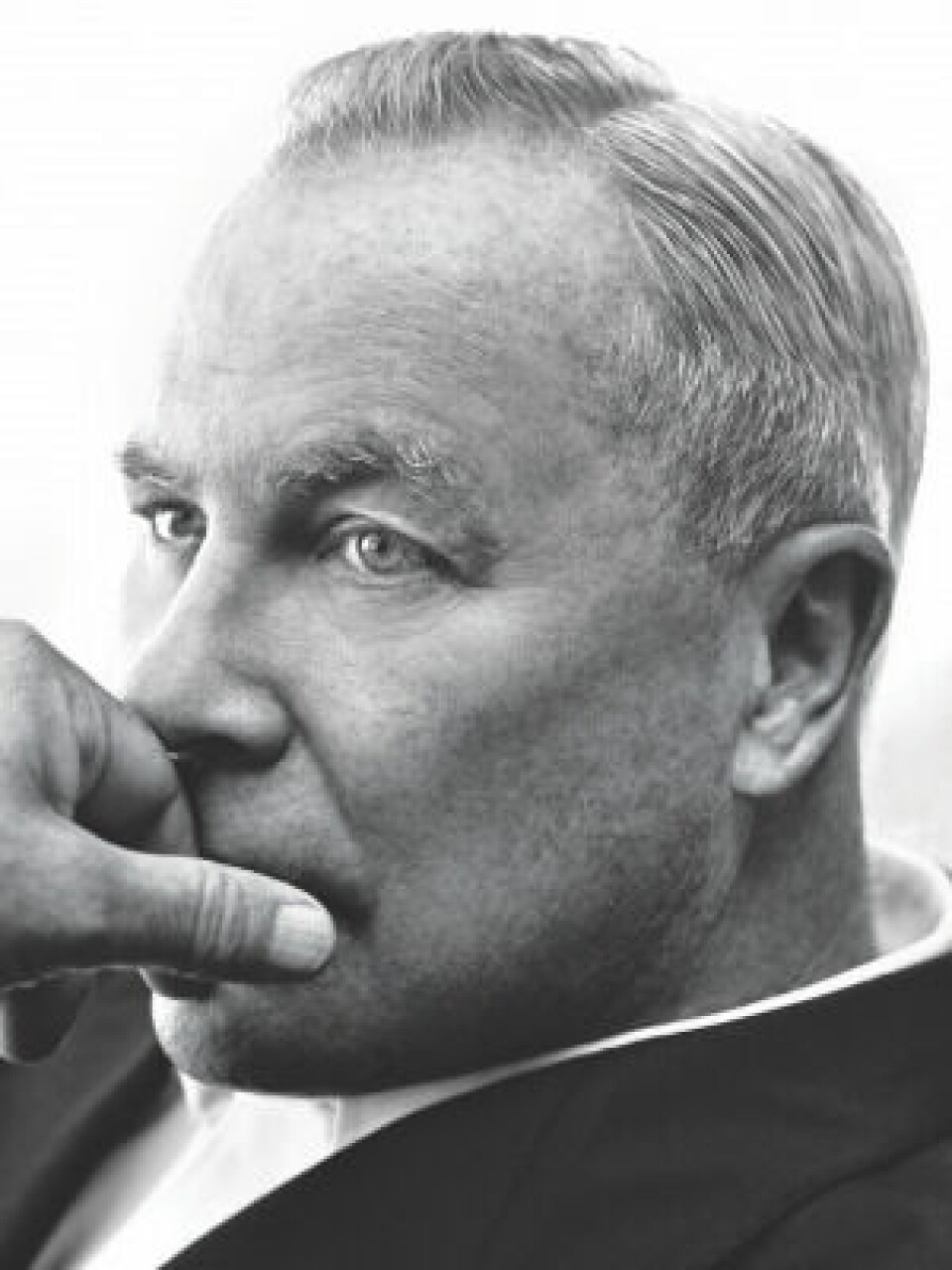

The only constant is change

Robert Wilson talks with Bergen International Festival director Anders Beyer on form, the future, the past and a production he dreams of creating in Bergen: A music theatre performance on Herman Melville’s «Moby Dick».(This is the original, English version of the interview published in NST 1 2021).

Anders Beyer: This conversation will not be centered around the current situation with the pandemic, but I have to ask: How are you, and what does your daily life looks like in these uncertain times?

Robert Wilson: It has given me time to think and to reflect about future works and much needed time to make drawings.

AB: You’re in Europe right now. Are you reluctant to return to your homeland because of the pandemic?

RW: Yes. I feel safer here than in my own country. With the current situation, my work is in Europe, so if I left, I would not be allowed to re-enter the EU.

AB: Right now there are many things you can’t do. It’s difficult and not wise to travel, performances and festivals are cancelled, opera houses and theatres are closed. What occupies your mind right now? What is important to you with regards to reflections in life and in art?

RW: What is important is to keep on going and to have a presence, even when we are facing such a challenge. It is too easy to stop working.

AB: If my memory is correct, John Cage once said in his later years: ‘I’m not interested in my art, I’m interested in being alive.’ Is this thinking in any way relevant to you?

RW: Very much so. I will turn 79 on October 4th.

AB: How was it to grow up in Texas for you? Did you have opportunities for developing your talent?

RW: To grow up in Texas is not easy. I was born and raised in a right-wing, religious community. It was immoral to go to the theater or even to do social dancing. One could not walk down the street with a person of color. Segregation was everywhere. I knew I wanted to leave. There were no art museums, no theaters. It was a highly racist community. On the other hand, I will always be grateful for the beautiful landscape and natural beauty of Texas. The skies are unlike any other skies in the world. That landscape is in all of my will, even still today.

AB: How and when did you experience that the art domain was your destiny?

RW: I think I knew it from early childhood, but I was not allowed to express it, except in minor ways: the arrangement of the furniture in my bedroom, the organization I did as a child of kitchen cabinets and the pantry, where we stored canned goods and food. I was obsessed with order. It was the beginning of my interest in architecture and the organization of space, of lines and color.

AB: You once told me that your family is like any other ‘normal’ family. How did your family react when you, as a young man, gradually developed as an artist with quite radical views on art and in general deviated from what society perceives as ‘normal’?

RW: My family had no idea what I was doing, nor did they have the background to understand it. So, I went my separate way.

AB: When you were young, what inspired you the most during your search after your own voice and personal style?

RW: I was very inspired by two women who taught dance – ballet. They were called the Hoffmanettes. They were quite bizarre in their dress and appearance. They painted their faces white and made their eyes pop with blue mascara. They always wore blue orchids and blue skirts, similar to a ballerina skirt. They had a love for dogs and always had 30 or more white dogs, which were stray dogs found in kennels and shelters. They were artists. It was the first time I had met someone who was involved in theater and design. In addition to teaching ballet, they also worked with people of physical disabilities, athletes, children. They had a profound understanding of the body and how the body can heal itself. They often said, as Martha Graham said, ‘The body doesn’t lie. Trust your body.’

The boy who thought without words

AB: In 2017 the Shanghai Arts Festival presented yourLecture on Nothing. In connection with the performance, you told the story about your encounter with the boy Raymond Andrews. It was sotouching and interesting for the understanding of your work. Could you tell me about how you first met Raymond, the work Deafman Glance and your relationship to Daniel Stern?

RW: Raymond Andrews is a deaf, mute black boy, who grew up in rural communities in Alabama and Louisiana. The people with whom he lived had never seen a deaf person. He never went to school, and he was considered to be ‘retarded’ or ‘a freak of nature’. I met him when he was barely 13 years old. He had been sent from Louisiana to New Jersey. He had thrown a stone through a church window, and a policeman was about to hit him on the head with a club. I grabbed the arm of the policeman and said, ‘Why do you hit this boy?’ And he said, ‘It is none of your business,’ and I said, ‘Yes, it is. Why do you hit the boy?’ After some time, I left with the boy and the policeman, and we went to the station. After several hours of questions and talking, the boy was released. While walking to and being at the police station, I heard the sounds the boy was making and recognized them as being those of a deaf person. When leaving the police station, he led me down the street to a two-room apartment, where he lived with an all-Black family. Much to my surprise, they, too, did not understand completely that his problem was one of not hearing.

In the following weeks and months, I discovered that Raymond was going to be institutionalized. He had been tested by the state psychologist and by others, and was thought to be uneducable and a menace to the community, a boy who should be locked away from society. I questioned why it was thought that he was uneducable. I was finally shown an exam that he had been given. The exam was in words. As far as I could tell, he knew no words. He had no legal guardian. In 1967, I went to court, as a single man, to adopt him. This was highly unusual for that time, and it would be at this time, as well, for a single, white, gay man to adopt a Black boy. At the end of the proceedings, when speaking to the judge, I said, ‘If you do not give me the boy, it would cost the state of New Jersey a hell of a lot of money to lock him up.’ And the judge said that I had a very good point. So, he came to live with me. I thought that I thought in words. And, I thought that Raymond was intelligent, perhaps highly intelligent, and it became apparent that he thought in terms of visual signs and signals.

At this time, I had met Daniel Stern, who was the head of the Department of Psychology at Columbia University. I met Dan through Jerome Robbins. His special study was in preverbal communication, between mothers and their infants. Dan was particularly interested in Raymond and how he saw and understood the world, without thinking. In the following months and years, I began to collect images that Raymond drew, and I made notes and observations on things he saw. He would see things that I did not notice, because I was preoccupied with what I was hearing. At one point, I took my notes and decided to make a theatrical work with him. And, during the course of two to three years, I put together a work that I called Deafman Glance. I produced it myself and showed two and a half hours of the work in New York. The total length of the work was seven hours. Jack Lang, the head of the festival of Nancy, saw the work in New York, and he invited the work to come to the Festival of Nancy for two performances. As a result, fashion designer Pierre Cardin saw it and invited me to Paris, to show it in a very large theater which seated 2,500 people. French poet Louis Aragon wrote a letter to his (then deceased) colleague André Breton after the performance,[1] and he said that it was the most beautiful thing that he had seen in his life and that it was what they hoped would be the future.

I was encouraged by Dan Stern to produce Deafman Glance. I saw, in 1967 and early 1968, over 250 16mm films which Dan had made. These were shot in a natural situation when a baby would cry and a mother would reach down to pick up her child. Stern slowed the film down, so that you could see what was happening frame by frame. There are 24 frames in a second, so one could look at 1/24th of a second. In eight out of ten cases, the initial reaction of the mother was that she was lunging at the child and that the child was reacting. The next two or three frames, the mother’s attitude was completely different. The next two or three frames – again – something totally different. So, in one second of time, the situation between the mother and child was very complex. The mother, seeing the films, was shocked, especially seeing her aggressive reaction toward the baby. Her reaction was, ‘But I love my child.’ So, perhaps the body is moving faster than we think. There is a language there, almost imperceptible. At the same time as Dan was working, American philosopher Susanne Langer talks about the ‘impingements on the body’ as a language. It was these almost imperceptible movements which Raymond was more readily reading.

AB: Your relationship with Raymond started in the mid-1960s. You used the story about the violent policeman to send a statement aboutBlack Lives Matter. Your statement ended with this reference to Raymond: ‘This was 1967. Every day since then, a person of color has been a victim of continued police brutality and structural oppression in the United States of America. To our protesters: Now is the time we must hear your voice. To our leaders: Be careful. History is recording you.’

RW: It was not that I was so involved with social justice, but it was a genuine fascination with how Raymond thought and how we would and could learn about the world. There was no place for him, he was being locked up in a delinquent home. He had no legal guardian, and as a result, I convinced a judge in 1967 to let him come and stay with me. I became his legal guardian. With him, I wrote my major early works in the theater. They were all silent.

An apple and a crystal cube

AB: Why did you create the Water Mill Center and the foundation?

RW: I created the WMC, because I wanted to move from Manhattan to a natural environment. Since 1965, I had a studio/loft space at 127 Spring St., where all of my early theater work was developed. I wanted to be close to nature and out of the noise and bustle, rush, of the city. So, I chose to go to Long Island. I love the light there. The island being this long strip of land in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. It was a spiritual awakening for me.

AB: During a meeting in Madrid, you told me about your creative process. You made a drawing to illustrate how you create a new work, how you think about structure and more. Could you explain how you form a new piece by referring to this drawing?

RW: The best class I ever had at school [Pratt Institute Brooklyn] was taught by Sybil Moholy-Nagy, who taught a course on the History of Architecture. It was a five-year course. In the middle of the third year, she said, ‘Students, you have three minutes to design a city,’ and she took out a stopwatch and timed three minutes. Then she said, ‘Time is up, turn in your papers.’ I drew an apple and inside the apple, I put a crystal cube. And she asked me ‘What is this?’ and I said ‘It is a plan for a city. Our communities need something like a crystal cube at the core – at the center. A place where one can go for enlightenment, when one could see the world, the universe. Like a medieval cathedral in the middle of the village. It was the highest point, a place where anyone could go, rich or poor. It was a place where artists showed paintings or made music. It was, in a sense, like a crystal cube inside of an apple.’

What I learned from this class was to see the total picture of the situation quickly. In all of my works, I make a diagram, so that I can see the whole, quickly. The Life and Times of Joseph Stalin, 12 hours long, had a circular, seven-act structure, with one and seven mirroring each other – two and six mirroring each other – and three and five mirroring each other – with the fourth act in the center and as a turning point. Einstein on the Beach is in four acts, with three themes. It had a structure of theme and variation, it did not have a narrative. But I could see the whole, quickly. If theater is not about one thing, it is too complicated. When it is about onething, it can be about a million things.

AB: You always work on several productions simultaneously. Can you reveal some of the ideas that the world will see in the coming years?

RW: I am currently preparing an exhibition of drawings using charcoal. They are based on Mozart’s Messiah,an opera which I am also preparing. I have been asked to create a work for the anniversary of Dante in 2021. I am preparing a film with Phillip Glass and Godfrey Reggio. There is a new dance work with Lucinda Childs, that is being prepared in Toulouse. I am setting a project to be performed in Indonesia called The Lady. I have plans to reopen the Watermill Center with a new Residence building.

The art world will always be the same

AB: Why do you like the idea of making Moby Dick into music theatre?

RW: I usually choose a subject that I feel is right for the country in which it is going to be performed. Somehow, Moby Dick seems to be a good fit for Norway and Bergen. I like the drama of the story and reading through the text, I hear music. It is a classical story, and for these reasons, I am fascinated by it.

AB: You have worked with some of the leading forces within all art forms, actors, singers, musicians, composers etc. Once you mentioned Lady Gaga to me. In future productions, who do you dream of working with?

RW: An artist who fascinates me right now is Carrie Mae Weems – her narratives, her texts, her visual sensibility, and her concern for human rights and social justice. I am hoping very much to realize a new work with her. She is one of the most exciting artists that I know today.

AB: Now, as we gradually begin to get the feeling that this crisis can go on for years, there are reasons to think deeply about how cultural life can not only survive but actually thrive in this new reality; a reality we can expect to persist in one way or another even when the crisis is officially over. At the global level mankind may have been so affected and alarmed that our collective behavioral patterns will be changed for a whole generation. Do you see any hope for the future in the art world?

RW: The art world will always be the same, and it will always be constantly changing. Take a few seconds to listen to the sounds in silence. The sequence of sounds that you just heard will never recur. So, the only thing that is constant is change.

[1] Aragon, Louis, et al. ‘An Open Letter to Andre Breton from Louis Aragon on Robert Wilson’s Deafman Glance.’ Performing Arts Journal, vol. 1 no. 1, 1976, p. 3-7. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/654658.