Life and death in people and books

(Amsterdam/Oslo): How can we be in proximity with (auto)biographical fact without digging into, or excavating the real lived lives of people? The performances She gave it to me I got it from her by Clara Amaral and En lys sommers usigelige smerte by Mette Edvardsen open this question by allowing the time of the book to meet the time of the performance, and by giving its audience a precious performative gift.

You write a review because you have been asked to assess a performance: is it good? Is it bad? Worthwhile or not? You write

about performance because you want others to see, or you want to share a way of seeing. Maybe you try to put the performance in a context that might not be self-evident. You add. Sometimes there is a desire to document what has taken place: an observation, a feeling, a thought. Sometimes you want something of the performance to linger, a little lasting longer. Maybe we re-view in an attempt to ‘re-see’. Some reviews just happen. This is one of them.

For, with and about hands

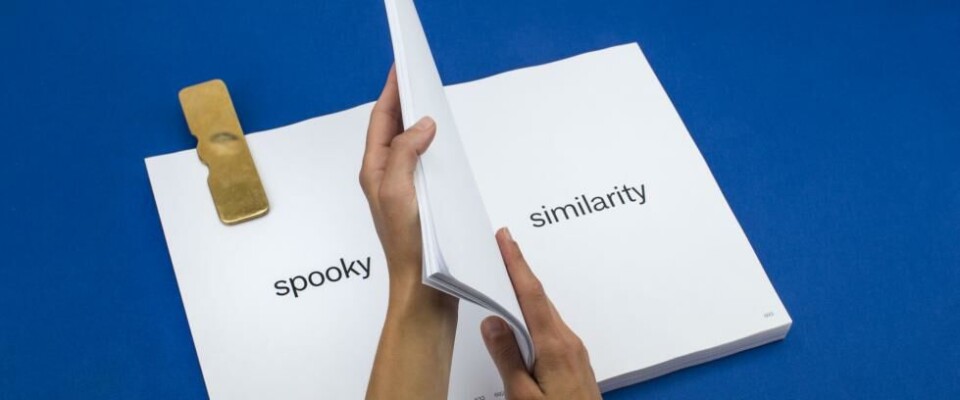

Both a book and a performance, She gave it to me I got it from her departs from a snippet of Clara Amaral’s family history, tracing back five generations of women while simultaneously leading its audience (and readers) to a kernel of a simple hand gesture: a signature. We are in a room with a table covered with cobalt blue cloth. Amaral positioned on one side, the audience on the other. In between us, a thick book with something scribbled along its spine.

The book, one could say, holds a poem. A poem to be performed and a story to be told. Amaral flips through the pages, a lick on the index finger for each turn. The telling of the story is handled with care, though not always carefully. Pages are not only read, but also ripped out, rearranged, repeated, hidden under a stack and put aside––a process of dismantling. We see choreography for, with and about hands. At the end of the performance, the book now mostly a stack of loose papers, I suddenly think of ‘autobiography’, a word of which I am usually suspicious, but which, having arrived here, rings true.

Signing for the sake of art

I’m wondering if describing the actions in She gave it to me I got it from her is the right thing to do. I fear, more than with many other performances, that it could take a kind of subtle magic away. I am thinking of the number 150 that Amaral mentions in a contract she reads out loud at the beginning of the performance. Normally only 5 audience members can attend, she tells us. And as there are only 150 copies of the book (and some will only be read and not performed), an estimated calculation informs me that even in the most optimal production scenario only 750 individuals will see this performance. While pitying anyone who won’t see She gave it to me I got it from her, I also revel in the conceptual premise that attending this moment is somehow special, almost exclusive. And so, without really understanding what we are agreeing to, we spell our names out loud so Amaral can put them in, then take the pen and, one by one, sign the contract.

One could say art always holds a contract with its audience, even if it’s rarely outspoken. The last time I signed a document for the sake of art was for The Probable Trust Registry: The Rules of the Game #1-3*, a solo exhibition by the conceptual artist and philosopher Adrian Piper, where visitors were invited to agree to a series of ethical commitments. I remember reading the proposals and feeling unsure if I could stand behind them. Eventually, I only signed up for one: to ‘always mean what I say’, half driven by curiosity about what would happen next, and half by a desire to actually give it a try. A couple of months later, when the exhibition was taken down, I received by mail a ten page long list filled with tiny names (including my own) and that was that. Nothing happened afterwards, no further questions were asked.

Admittedly, I don’t feel entirely at ease with my signature becoming part of an art work. Then again, I am constantly agreeing to policies, terms and conditions on the internet that I haven’t even read. Not that I don’t care about my right to privacy (I do!), but these texts are written in such a way that it would take me a year to understand what they’re actually about. Knowing that She gave it to me I got it from her deals with the repercussions of illiteracy in the past, I am reminded of new forms of digital illiteracy and how vulnerable it makes me, and us, as well as the status of the signature.

Tracing a family genealogy, you might find yourself staring at a cross on a piece of legislative paper, a sign of possible illiteracy, an educational system not yet in place –– or if in place, excluding especially women and the poor. In the case of Amaral’s lineage, because of the late educational reform in Portugal, the illiteracy of her grandmother, a cultural inheritance from the previous generation of women in the family, is a living memory. In performing this autobiographical fact, and through the deconstruction of the book, Amaral points towards a generational exchange and its inherent feminst dimensions. She gave it to me I got it from her gives the audience a glimpse of a most intimate moment: An image of a hand holding another hand, a precious seed of autobiography thrown into a lake of conceptual abstraction where it lingers around without the need to take a particular shape –– as if in suspension.

Attending

This ‘performative suspension’ is something that also resonates in and around Norma T, a space recently initiated by the

choreographer Mette Edvardsen, which functions as ‘a project room, an occasional bookshop and a fictional friend’, and hosts events and performances such as She gave it to me I got it from her. When visiting Norma T, the audience is offered a poster calendar, the kind people hang on the door of their toilets. For the upcoming months, it shows there will be regular activity taking place, all of it tracing back to a relation between books and performativity. While later events added in handwriting indicates that Norma T’s program is in a state of becoming, the emptiness from January onward reads both as a commitment to time, and an undoing of the pressure to have it all planned out.

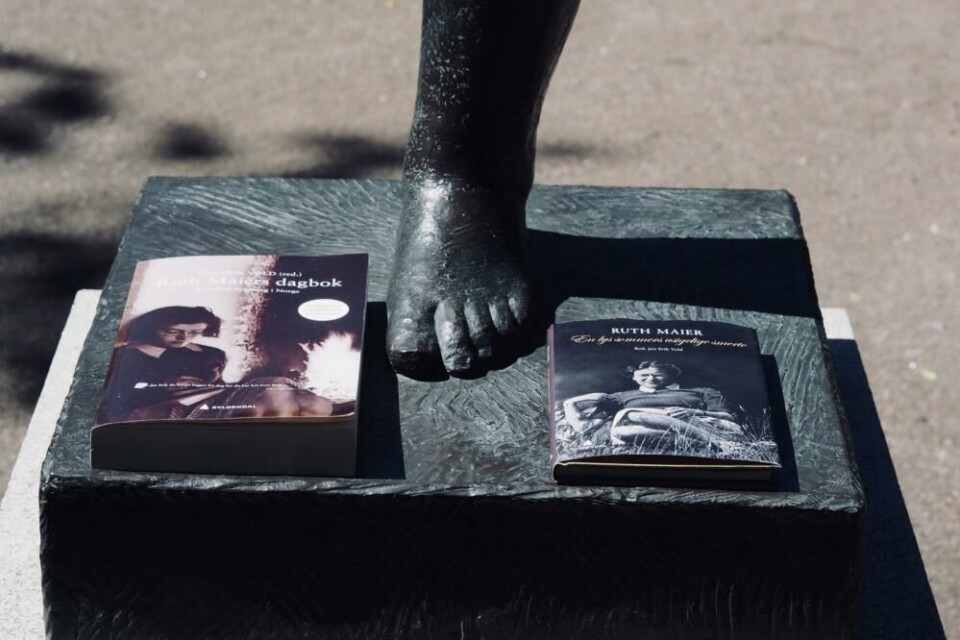

Watching a performance in the context of another artist’s practice, offers new ways of being in attendance. Amaral’s performance overlaps with several interests also present in Edvardsen’s work and vice versa. Instead of seeing one’s artistic interest as in competition with others, Norma T provides a context to see the work relationally. In this sense, She gave it to me I got it from her brought me back to my experience of En lys sommers usigelige smerte (A bright summer’s unspeakable pain), a performance by Edvardsen with its title borrowed from a poetry collection by Ruth Maier. Spread over several weekends, bridging the end of the summer with the beginning of fall, En lys sommers usigelige smerte invited the audience to gather around a sculpture for which Maier modeled, and learn one of her poems by heart. However different from She gave it to me I got it from her, Edvarden’s performance in a similar way carried an element of biography brought to life by the performative (in this case collective) action.

Ruth Maier was a Jewish writer who fled from Austria to Norway in the late 1930s and was subsequently deported to Auschwitz, where she died. Her diaries were kept by her lover, the poet Gunvor Hofmo, until she died in 1995, and later published, in 2007. The performance of En lys sommers usigelige smerte evokes, on the one hand, the joy of learning a poem, the assemblage of images, visual notes sculpted in the mind. On the other, the weight and horror of what happened to its writer and the fate of millions of Jews. En lys sommers usigelige smerte reminds us that memorials can take many forms.

How can we be in proximity with (auto)biographical fact without digging into, or excavating the real-lived lives of people? Both She gave it to me I got it from her and En lys sommers usigelige smerte open this question by bringing together the different temporalities of the book and the performance. Conversely, by attending to their performative proposals, and by observing or trying out a kind of ‘doing of the written word’, we receive something that we carry with us after the experience of the performance––a gift. Something sculpted in our minds and in our imagination. Something to recall in the future when we want to remember what we have seen. Something that can make us, in so many words, see it again.

* Adrian Piper, The Probable Trust Registry: The Rules of the Game #1-3 , Hamburger Bahnhof Berlin, 2013-17.

(Published 10.17.2022)