Going Naked

Onstage nudity served as free content for pornographic websites? These days it’s just a click away. This phenomenon affects performers disproportionately and raises questions about artistic freedom and ownership of one’s own image in the digital era.

TheNorwegian translation of Ilse Ghekiere’s text has been printed in the # 2-3 issue of Norsk Shakespearetidsskrift 2024. By the time of online publication, the English version had been slightly revised.”

Once in a blue moon, I google my name with the word “porn” next to it. It’s something I started doing after a few of my colleagues, all dancers, discovered images of their naked bodies on pornographic websites. These were not cases of sexually explicit revenge porn, posted online by ill-meaning ex-lovers. These were professional images: pictures or video stills of dancers just doing their jobs, albeit naked jobs, on stage. Considering I often performed “in the nude” early in my career, the chance that a revealing picture of my younger self was out there, didn’t seem unrealistic.

These cases first came to light with the advent of the MeToo-conversations in the performing arts. That said, they didn’t exactly fit the typical MeToo sexual harassment scenario. Often it was not clear who the so-called perpetrator was, nor did it involve direct confrontation between individuals. Rather, the problem here was the image – an image out of one’s control, no longer belonging to oneself, but to others.

“Porn,” “nude,” “pussy”

I first encountered these images through a case about a live-stream video. A Belgian company, renowned for its so-called, radical dance and theatre, left a live recording of a performance – saturated with explicit scenes – online for several months. It was unclear if this live-stream was the result of sloppy management or part of a promotional plan. However, still images from the live stream soonappeared on countless pornographic websites – even revealing the identities of the dancers. The images were often juxtaposed with sexual comments such as: “Keep stroking that little kitty.” When I entered the dancers’ names in a browser with words like “porn” or “nude” or “pussy,” a never ending grid of naked performance pictures – often with zoomed-in detail of their genitals – would fill my screen. There were also videos, some of them watched more than 100,000 times. One dancer wrote to me: “It feels as if that number, those 100,000 times, equals the amount of time my physical integrity was violated.”

Around the same time, I received an email from a group of dancers in Hungary who discovered that someone called “Season of Monsters” was posting pictures of naked performers on a blog called “Theatrical Erotica.” At the start of the page, the anonymous blogger described the project as a way of “bringing together visuals”from the Hungarian theatre scene that could, according to this person, be labelled “erotic”. The introduction, written in a tone of self-declared authority, presented the pictures (and people) as if they were collectors’ items in an honourable project for the collective good.

Réka Oberfrank, one of the dancers whose image appeared on the blog, told me in a recent conversation that she was especially shocked that the blogger found portraits of her and her colleague as adolescents. The blogger added their smiling young faces and full names to their naked pictures. This juxtaposition of nudity, framed as erotica, alongside their innocent adolescent portraits was consistent throughout the set up of the blog. Under each post, people were invited to leave comments.

While much of the content on the blog could be traced back to promotional material that artists posted themselves, at first Oberfrank didn’t understand where her pictures came from. The performance in question was filmed but she never posted any pictures online. Then she remembered a cameraperson showing up unannounced, just before the premiere. Oberfrank’s performance was part of a youth-talent program and many of the choreographers (including Oberfrank) were showing their work in front of an audience for the first time. It was a big deal. It turns out the cameraperson was sent by the program as part of a similar initiativefor young critics. As she remembers it, Oberfrank didn’t object to being filmed; however, she now realises she wasn’t able to assess the situation clearly due to the pre-premiere combination of stress and excitement. Eventually, without her knowledge and permission, the footage was used as part of a series on YouTube in which young critics contextualised the performances in the program. Soon after the YouTube series was produced, the still images of the video appeared on the “Theatrical Erotica” blog.

In a first attempt to gain control of the situation, Oberfrank’s colleague reached out to the person responsible for the YouTube series and asked for the images to be taken down. This person, who also happened to be an important critic in the Hungarian theatre scene, replied that they had “nothing to be ashamed of.” The YouTube-video remained online and “Season of Monsters” continued to expand their “collection.”

When Oberfrank and other colleagues wanted to take further steps, they were confronted by another issue: not every dancer who appeared on the blog saw this presentational context as a problem. There was no consensus on how to feel about these pictures being online in this context. While some felt their integrity was deeply harmed, others shrugged it off as part of the job – a risk you take when you perform in the nude.

Of course every individual is free to feel what they feel. Some might say that having one’s picture taken while naked on stage and then complaining when it ends up online is not only naive, but hypocritical. Others might say it’s the shift in context that poses a problem, reinforcing some kind of “moral dichotomy between art and pornography.”* Why is it that the naked body in the context of dance (or art in general) is seen as more sacred than the nudity of a glamour model or porn star? Some people might even argue that this feeling of victimisation comes from a sense of hostility towards pornography and sex work. That said, you don’t have to feel victimised in order to speak up against a violation of your rights. Even if you are a performer who does not see a problem with your image appearing in the context of porn, you might want to ask yourself whether it’s OK that someone else, a total stranger, is financially (or privately) benefiting from your naked image. Sex workers too, would be rightfully concerned by that kind of unwarranted exploitation.

It’s fair to assume that part of the reason viewers find these pictures exciting to look at is because these images were not intended as pornography. It’s precisely these layers of exploitation (this was not meant as porn, these are not sex workers, these people did not agree, or know, that this was happening) that turns certain people on.

The impact these pictures being spread online, doesn’t end there. Dancers and actors, who have experienced similar events, have reported unwanted “fan groups” following them on social media. Out of nowhere, they sometimes receive private messages with sexualised comments about their bodies, followed with links to the pornographic websites. One performer I spoke with compared the experience of digital harassment to “being raped” and preferred I leave out the details of her story in this text. Still in therapy, this woman continues to fight anxiety and stress that is a direct result of the psychological terror she was subject to online.

My image is my profession

The Norwegian law, at least in principle, is very clear about the use of another individual’s image: you cannot publish someone’s picture without their permission. But even though the above mentioned cases might sound like an obvious violation of the law, finding justice has proved to be complex, not least because it involves the internet.

If you are a performing artist your image is your profession. However, when working for someone else, your image, your rights and your say, might be altered significantly. When you dance or act in a performance, your dancing and acting become part of the work of art, and, consequently, so does your body. At some point, a choreographer, director or company will record their work for reasons of promotion, selling, archiving, etc, and will need the performers’ permission to use the material. Any legal expert will advise the author or company to get a release that is as general as possible and avoid the possibility of any future discussion about authorship or royalties. For example, imagine a choreographer has a retrospective 10 years down the road and wants to use the recording of the performance in an exhibition. In that case, choreographers don’t want to be bothered with tracking down and collecting each individual’s consent. After all, there is logistic convenience in having you (and all your rights) become part of their work of art.

In the live stream-case in Belgium, all the dancers signed a payment contract in which they handed over a significant part of their “neighbouring rights” to the employer. Neighbouring rights, simply put, are rights that protect the legal interests of persons and legal entities that contribute to making a work, while not being, in the conventional sense, the “author” of that work. In a conversation with law professor Irina Eidsvold-Tøien, she explained that in Europe, performers don’t have copyright but instead have “neighbouring rights.” Even though this structure is weaker than copyright protection, it can, in theory, be used by the performer to control their contribution and contractually negotiate financial compensation whenever a performance is staged, screened or streamed online. By signing away their neighbouring rights, the dancers denied themselves any financial benefits resulting from a successful distribution; they also signed away the right to say anything about the ways in which their image could, or would, be used.

When we talk about ownership and responsibility in these cases, we need to grapple with a legally defined constellation of numerous parties who all claim different degrees of ownership. While copyright is linked to the “author” of the performance, a “picture” of a performance will most likely be copyrighted by the photographer. Consequently, as seen with the case of the live stream by the Belgian theatre company, there might be yet another party who owns something called “exploitation rights” for the recording of the performance and its distribution. So which rights are left for the performer? A performer whose talent, body and image are at the centre of the work itself?

Eidsvold-Tøien refers to the question of the performer’s image as “a hole in the neighbouring right structure: There is no copyright for the way a performer looks, dances, walks, or speaks, … basically there is no protection for their expression. That said, when performers feel that their image on stage has been violated, they can always rely on their fundamental human rights, such as personality rights and privacy law.” Therefore, even if someone juridically “owns” an image of you, they don’t get a free pass. If people use your image in ways that harm your reputation or integrity, they are violating your basic human rights. Proving that your reputation and integrity has been violated might sound tricky, but in the context of law, non-consensual spreading of naked pictures quickly crosses a line.

Cease-and-desist

How do we act on those rights? And whose responsibility is it to act? The Hungarian dancers soon realised that collective action would be challenging. Oberfrank went to the police; the case was dropped within a few weeks time. Once it became clear the dancers might need to raise money for a lawyer to move forward, people began to quietly withdraw their engagement. When asked if the group tried to contact the blogger, Oberfrank said the blog had no contact information attached to it. She recalls feeling alone and let down by the system, deprived of her rights. Together with her colleagues, she decided to give up.

I wish someone could have told Oberfrank that even Hungary, a nation under an extreme right government, has its own version of image rights written into the constitution. According to that law, Oberfrank’s rights to privacy were definitely violated. I wish that someone could have told her that even if there was no email address on the blog, contact information can be found through a website’s domain name. That said, maybe none of this would have made a difference. Most importantly, I wish these dancers would have received free legal support – someone to clean up the mess for them. Someone like a hacker. I definitely wish there were more feminist hackers out there.

But even in the situation of the live stream in Belgium, where many lawyers were involved, it was shocking to observe the near impossible task of removing the images. One dancer said: “I have the feeling that everytime I click on one of those links, it spreads to at least two other websites. It really feels like a virus.”

The plagiaristic use of the dancers’ image from the live stream was first and foremost an infringement on the author rights of the company. Considering the company also failed to protect the privacy of their employees, the dancers could have, in theory, sued the company. This legal tension probably explains why the company suddenly jumped into action and offered to cover juridical costs.

However, after the first cease-and-desist letters were sent out, it became clear that the company’s lawyers were not putting the necessary effort in. The dancers, (as if they didn’t have anything else to do) were expected to search the internet for their own images and report them to the lawyers. The company claimed they cared about stopping the spreading of the pictures but their actions spoke otherwise. The dancers felt let down by their employer and the juridical structures in place. To this day, many of the pictures and videos are still out there, available for consumption.

Problems with nudity

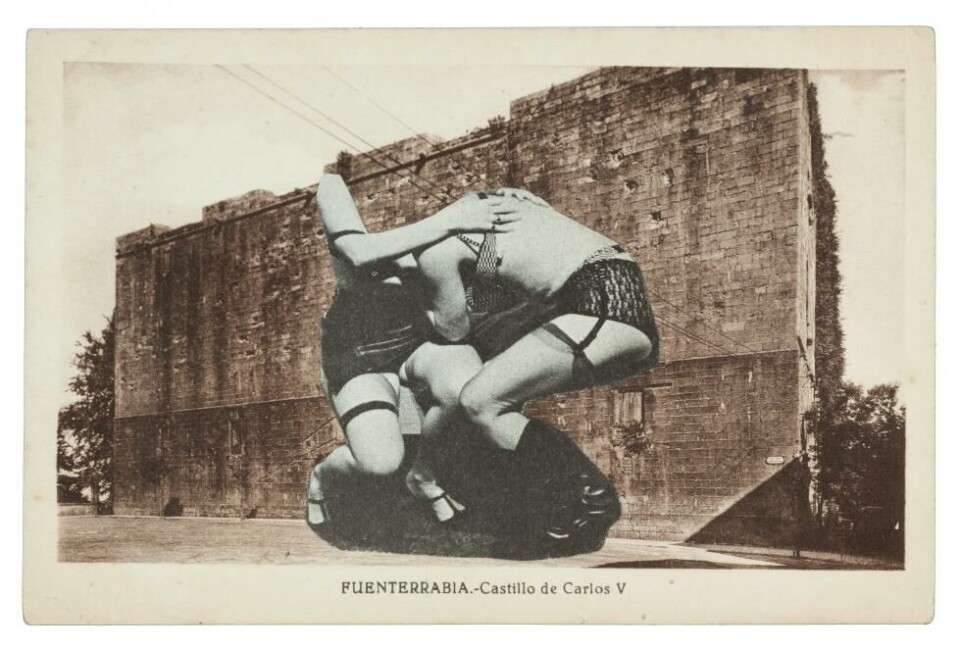

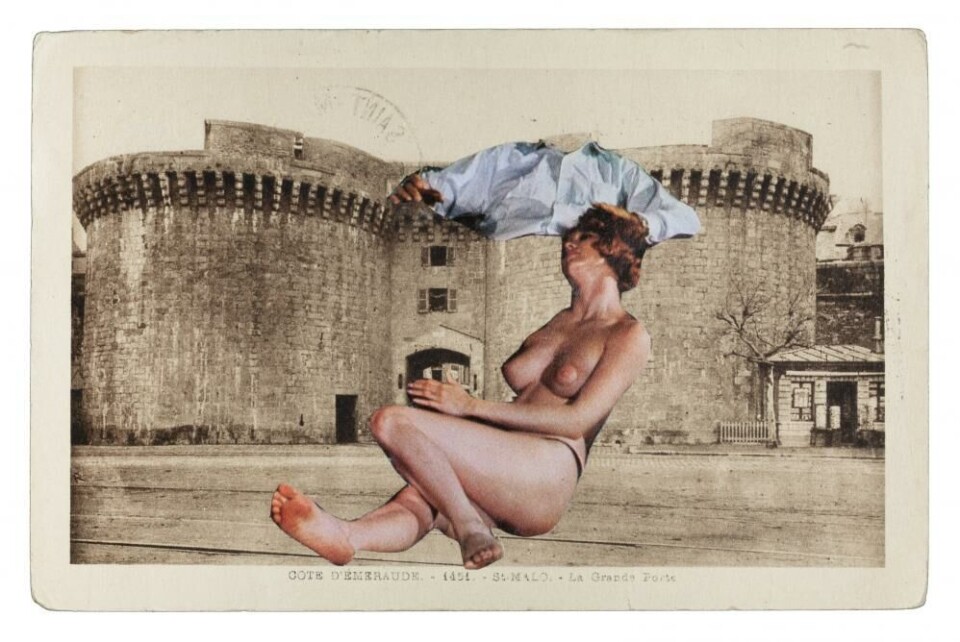

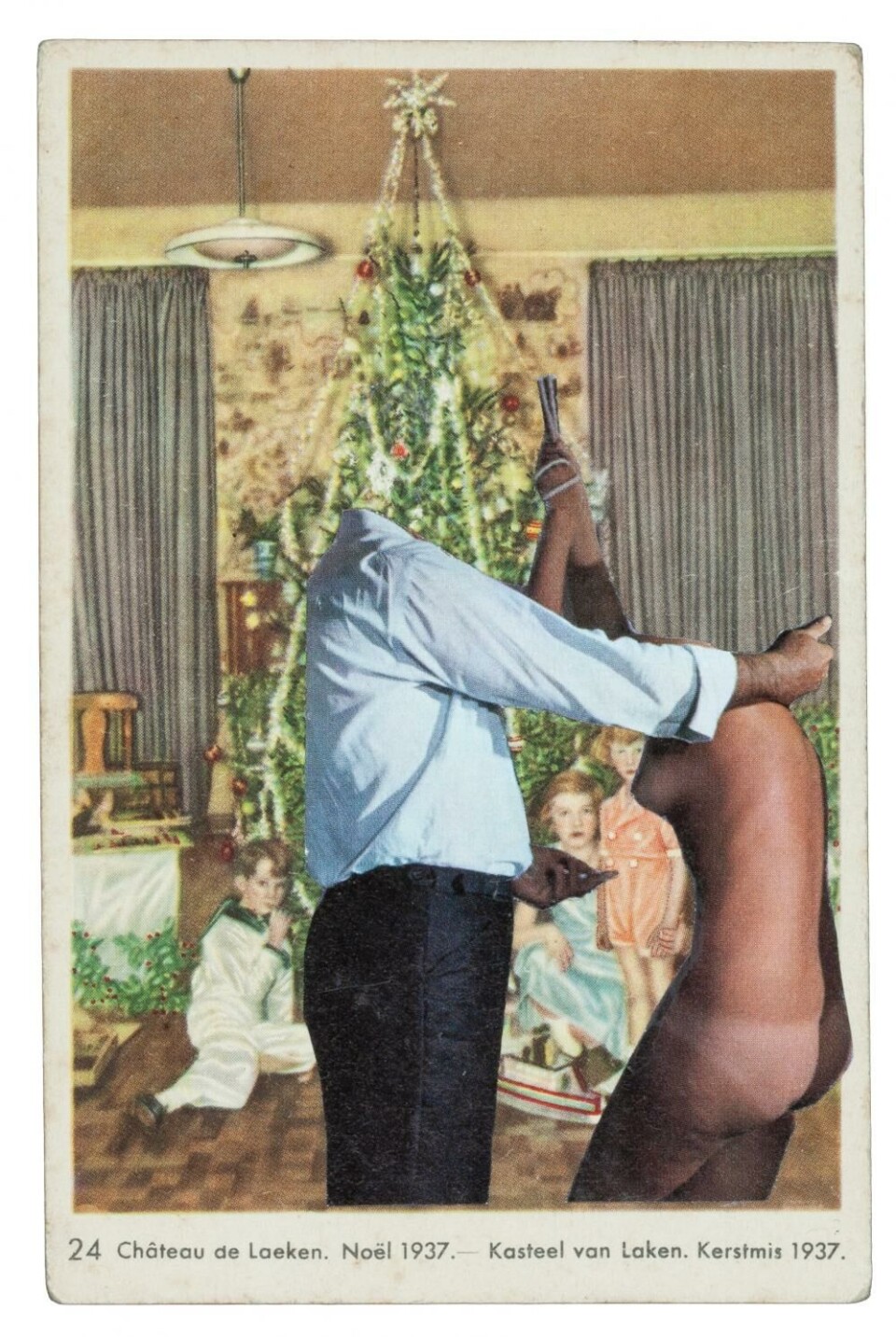

Apart from all the legal and ethical questions, these cases also raise several interesting artistic questions. What is the difference between nudity in art and nudity in porn? Why does a shift in context matter? If some performance art can be turned into porn with just a few clicks, maybe that says something about the art in question? Or what if the tables are turned? What if, instead of seeing this as a problem, we embrace the transgressive potential of this new cyber era; a time in which all images can be taken, used and manipulated by anyone: creating a total loss of self.

One problem with the conversation about nudity in the performing arts is that it’s often stuck with the trope that art needs to defend the naked body as an expression of freedom. I am not dismissing this argument (the freedom of the naked body is important), but there seems to be a naivety, even blindness towards today’s rapidly shifting status of the image. With the rising number of so called deepfake nudes – shockingly realistic AI-generated pornography created from people’s “real” image – the onus is on the art world to face up to a new set of complexities, the likes of which we have never witnessed before.

What makes performing art intrinsically different from many other disciplines is that it happens in the moment: it’s live and in many ways, ephemeral. It also, almost always, involves real people on stage. The stage is a place where dancers have agency. (Of course, there will always be those spectators who have different intentions. The image of the same three men sitting on the first row of every flesh-showing performance, comes to mind. It’s annoying – I have been there – but at least you can “work with it.”) From the moment the performance is captured – in a picture, moving or still – the dancer’s image, body and actions become part of an object they no longer have agency or ownership over.

In the last decades, changes in technologies – the emergence of the camera-equipped smartphone in particular – have shaped and altered the fleeting qualities inherent in a live act. Look at the ocean of screens held high at any popular music event. Furthermore, it’s not only the audience that take out their phones during a performance to capture what they see and spread it online. Artists and art institutions go to great lengths to promote their work by documenting, showing, posting and spreading as much as time and money allows. This “making content by taking it out of context” has become a crucial aspect of the distribution of art on stage; consequently, making the status of the image of the performer all the more more precarious.

Better practice

People tend to approach the Internet as an omnipotent monster they have zero control over. While aspects of this statement are true, we need to inform ourselves and make decisions accordingly. Since these cases involve not only dancers, but also choreographers, directors, photographers, theatres and audiences, we should collectively try to ensure that people’s rights and images are protected.

In the wake of MeToo, there were some “better practices” installed to protect images of performers naked bodies. These changes came about as a result of demands from dancers. For example, in one performance, the performers didn’t do anything explicitly sexual on stage; however, the scenes were definitely suggestive, and naked. At some point in the process, the choreographers wanted to film the performance, which initiated an interesting discussion about the shift of medium and what that meant for the art work and the performers in it. As a result, the dancers demanded very precise contractual descriptions of where and how the film could be used. The contract also stated that in case of “non-authorized use of the captured performance or images,” the company would take “immediate action.” In short, informed and detailed agreements on the use of the performer’s image are already in practice. These practices should become standard.

Immediate action is crucial. Only one of the dancers who discovered their image on pornographic websites appears to have managed to stop the unwanted spreading of it. This action was taken because she fought it from very early on and from numerous fronts simultaneously. She wrote to all the search engines she could possibly think of and asked to have specific searches in combination with her name removed. Her lawyer contacted these websites. She also started a process with an equal rights organisation that used software to track and block images of victims of revenge porn. Her name may still pop up when writing certain combinations of words in the search engine, but the images are gone.

As I was writing this article, the Hungarian “Season of Monsters” blog, after being online for more than six years, suddenly went dark, with only a message referring to a server crash. Above it, a GIF showing Arnold Schwarzenegger’s face in dark sunglasses saying “I’ll be back” in a loop. The no longer functioning blog is now a tab next to my text. I click on it from time to time to check if it’s still inactive. Another routine added to the list. Once in a blue moon, I’ll still google my name (and some others) with the word “porn” next to it.

Note to the reader:

Except for Réka Oberfrank, other individuals did not want to be referred to by name. Their non-consensual pictures are still out there and they do not wish to draw attention to them. For legal reasons, I also needed to simplify each case. Pronouns of people are accurate. The gender of the Hungarian blogger is unknown.

If you are a Norwegian victim of the nonconsensual spreading of explicit images, please contact www.slettmeg.no. You can also preventively hash any explicit picture of yourself on the website StopNCII.org. If throughout the process you need peer-to-peer support, contact www.engagementarts.be.

The research for this article was made possible with the support of Kulturdirektoratet Arts and Culture Norway. It is part an artistic project about consent and the image rights of the performer.

Footnote:

*Van Brabandt, P. & Maes H. (2021) Kunst of pornografie?Een Filosofische Verkenning, 13.