‘What can we do that we can only do with time’

«Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine» is an ongoing project as part of osloBIENNALEN, currently interrupted by Covid-19. Initiated by the Norwegian choreographer Mette Edvardsen in 2010, «Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine» has taken on a variety of forms. Referred to as a ‘library of living books’ it has appeared as a reading room, an exhibition, a workspace, a publishing house and a bookshop. Recently, with the descriptive and all encompassing title Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine – A book on reading, writing, memory and forgetting in a library of living books, the project took the form of a book.

It is Christmas 2019 when I lay my hands on a copy of the newly published Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon

sunshine – A book on reading, writing, memory and forgetting in a library of living books. Already intrigued by the conceptual poetics of Mette Edvardsen, and by this project in particular, I am eager to dive into its pages. The next thing that happens is what happens with many books that enter my house: they start to live a slow life of their own, regardless of whether I am there or not. Eventually two seasons will pass before I get through the book in its entirety. Hence the out of sync arrival of this review. What can I say: a book is not a performance.

What can we do that we can only do with time? The question is posed by Edvardsen at the end of her opening essay, in which she meticulously describes how the project came about and how a method and a language took shape around it. It is a question that sits with me as I think about the pandemic now and how it puts the idea of time and perspective on a slippery slope. I’ve also been thinking about art forms and art practices that are, to use the word, immune against practical discontinuity and uncertainty. At the time of writing, Olso City has just announced that ‘all institutions for culture and leisure activities will be closed, apart from libraries’.

Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine has been around for a decade now. It finds its seeds in the science-fiction novel Farenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury and takes off just where the dystopia of that book ends. In the novel we face a world where happiness is being controlled, knowledge is systematically erased and books are being burnt. By the end of the novel, the protagonist joins a group of intellectuals who, in an attempt to preserve stories of the past, have decided to learn books by heart. It is precisely this idea of resistance that became the point of departure for the practice at the core of Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine: namely the peculiar attempt to ‘become’ a book by memorizing it word by word.

It is hard to talk about this publication without also talking about the experience of being a reader in the ‘library of living books’ first. I visited Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine for the first time during Kunstenfestivaldesarts in Brussels in 2017. Because I didn’t arrange the appointment myself, the experience took me somewhat by surprise. I didn’t know which book it was going to be, but as soon as the reading began, I recognized the author’s voice. A heat of discomfort began to fill my entire body and tears were already lining up, ready to descend, cascade style. With a hunched back and my eyes closed, I sat, unmoving, trying to hide my embarrassment as if I’d been caught. When the twenty minutes of reading came to an end, it was a relief that it was over.

Sometimes, without being aware of it, we become intimate with books like we become intimate with friends or lovers. An intimacy that is often confused with a sense of forbidden ownership: I am not Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf, yet I might feel I am.

Last summer, during the first months of osloBIENNALEN, I had a chance to visit Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshineagain, and enjoyed readings of Four Quartets by T.S. Eliot, Answered Prayers by Truman Capote and A Plague of Tics by David Sedaris. None of these brought on the tears, but the sense of intimacy continued to linger.

Each ‘reading’ of a ‘living book’ lasts about 20 minutes, which in itself might not be spectacular in a performative sense, but sitting so close to a person who has devoted hours of their life to remembering what they are telling you, brings about feelings of deep empathy and curiosity. The small talk afterwards seems in a way almost as much part of the project as the reading itself. In the same way, the publication appears as a continuation of these exchanges. Or, as underlined in the introduction: ‘This book, in spite of its apparent conclusiveness as a tangible publication and regardless of the sharp edges of its cover, has been conceived in continuation with a practice that has no apparent end.’

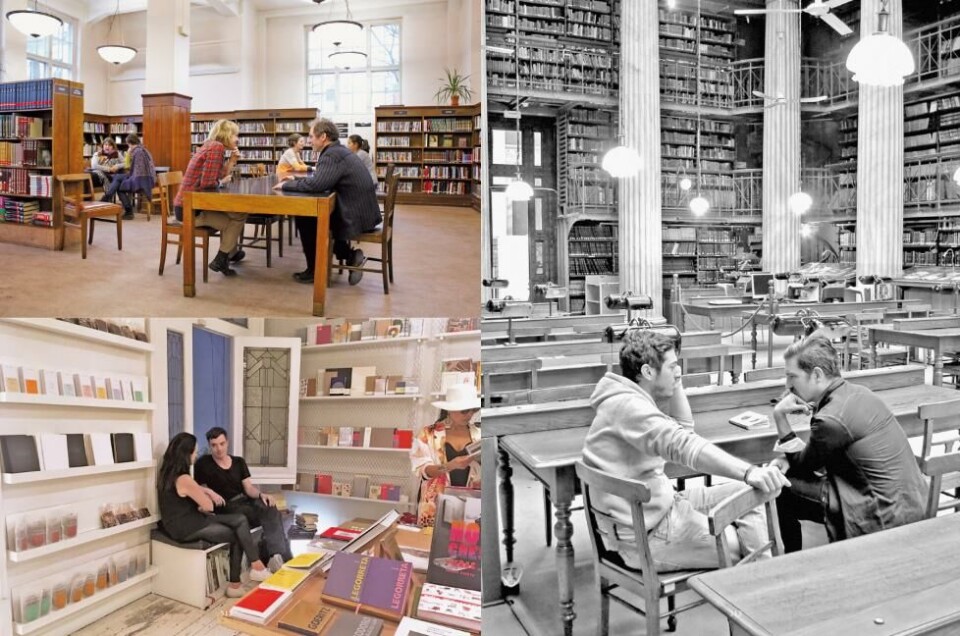

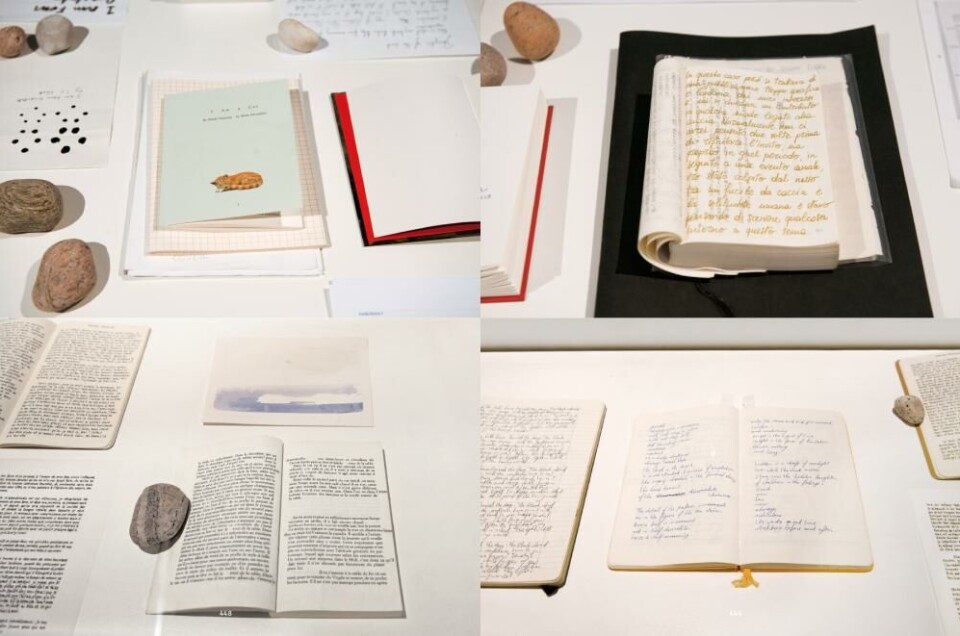

As book, Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine approaches itself via the genre of the essay. It balances between an urgency to document a complex artistic process and a desire to generate new materials and entrances to the work itself. The first part of the book consists of a collection of commissioned essays discussing a wide variety of topics related to the project. The second part is what the editors call ‘a visual essay’, containing pictures of one-on-one readings in and around libraries and exhibition spaces; of annotations on memorization; of books rewritten by hand from memory; of copies of books waiting to be remembered. In other words, the book is not the result of the project, but one of the shapes or even bodies the project will continue to let emerge. And so, it’s difficult to think of the book as an independent object, or as anything outside of the project as a whole.

While several essays have been written by the performers or ‘living books’ and are often quite personal, others have been written from the position of an observer or outsider. The essays by the living books are particularly appealing in how they give an insight into the ways in which the practice of memorizing intersects with people’s lives. Many of the stories, reflections and anecdotes reveal a level of obsession and idiosyncrasy as the essay-writer returns to the same book over and over (and over) again. One living book describes how memorized sentences appear in dreams, another book discovers after the hard labor of memorizing an entire book of poetry that there are different versions of the poems he has learnt, and one describes an impossible meeting with the widow of ‘his author’. ‘Even though I enjoyed being a ‘living book’, I couldn’t help but wonder now and then if I wasn’t wasting my time’, another one confesses. Each essay opens a world of its own and even though they connect through their subject, they feel also strangely apart.

What I find especially appealing and even touching about Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine and the stories described in this publication is that it revolves around a practice that is both generic and personal. The practice of learning a book by heart is also, or so I learn from several of the essays, an invitation that is in essence open to anyone. Meaning that, if committed enough, anyone can become a living book, and anyone can build up stories around it.

What I take from Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine and the book version in particular, is the idea of resisting time by being with time. We can decide to be shocked every single time our daily lives are restricted and interrupted, or we can expand our perspective and sit with something (or anything) longer than is expected of us. By returning to the art we already know, by looking for new entrances to what we have experienced before, by slowing down and stretching what it means to be an audience.