LAUDATION

The most sustained and important investigation of Henrik Ibsen’s plays in the history of theatre.

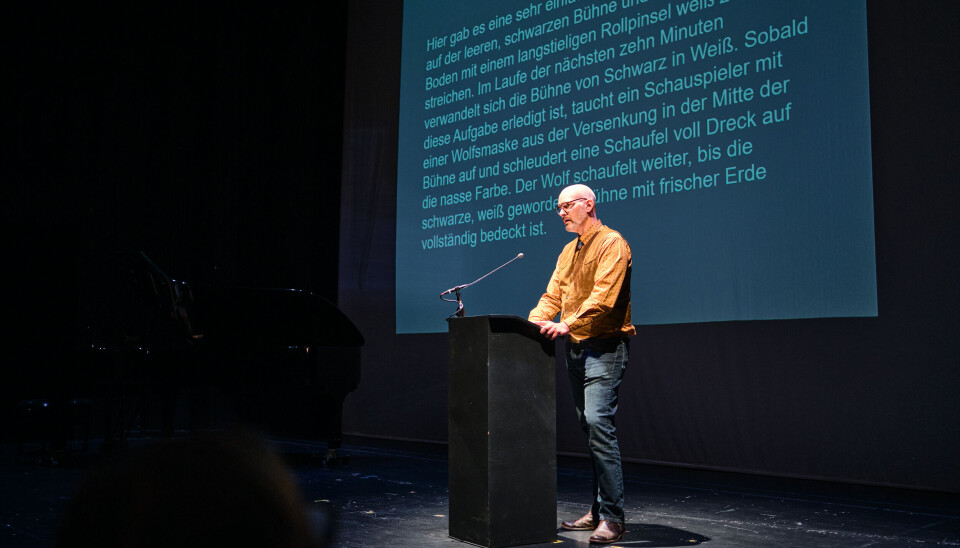

(Gießen): The Hein Heckroth prize 2025: Laudation for Vegard Vinge and Ida Müller, by Andrew Friedman.

Thank you to the Hein-Heckroth prize and Marcus Kiefer for their assistance and thank you to Vegard and Ida for inviting me to speak today. I am very honored and very nervous. I am honored because I have the privilege to tell you why I love these artists. I’m nervous because laudatory speeches are not common in the United States. The two genres of American speeches are Confessions and Sermons. So, I would like to begin with a brief confession followed by a short sermon. I have attended every one of Vegard and Ida’s productions for the past fifteen years, seeing more than two hundred and fifty hours of their art in Oslo, Bergen, and Berlin. I have written a dissertation, a book, and many articles about their productions, I have taught classes and given lectures on their performances. And yet, I do not understand much German or Norwegian. So, I feel compelled to tell you about the language in Vegard and Ida’s work I do understand.

Vegard and Ida’s art speaks for itself. It requires no translation. It is simple and direct: it imagines connections between Ibsen’s plays, the world, and the artists’ personal desires, and realizes those images in a fictional universe that is interrupted by reality. It is a war between fiction and reality staged in an Ibsen universe. It is the most sustained and important investigation of Henrik Ibsen’s plays in the history of theatre. But what makes those facts meaningful to me, why I have flown eighteen hours to stand before you for ten minutes to praise them, is that their art is driven by an old, but rare language. It is a beautiful language, and the artistic language I love most. The language in Vegard and Ida’s art that speaks to me is the language of the image as a commitment, the artwork as an ideal, meaning a way to live. It is not an aesthetic of originality or novelty, but of energy, of belief. It is an artistic language of demands. The way to speak this language is to practice it; to commit to the mission to become theatre’s greatest master builders.

In pursuit of the mission, Vinge/Müller are building a six-hundred-year project, the Ibsen-Saga. There is no authoritative production or performance in the Saga’s more than one thousand hours of stage art. Its open-ended running times, onslaught of images and sounds, fragmented and sprawling narratives, insistence that each performance is unique, incorporation of chance, and real-time direction, make it too expansive to be held within a single mind. Since 2006, the Ibsen-Saga has tirelessly grown. Their debut of A Dollhouse in Oslo was ninety-minutes; later that same year in Italy, the show ballooned to nine hours. Their 2010 Wild Duck in Oslo clocked in at nearly nineteen hours; the following year in Berlin, the production ran continuously for fourteen consecutive days. This project, which began as a unitary set in a black box theater now fills a national theater, a cathedral, nine shipping crates, and counting.

THE PROJECT IS ONLY IN THE FIRST QUARTER CENTURY of its mission. Vegard and Ida have a long way to go and much work ahead of them. And if they are successful, neither we nor they will see the Saga’s conclusion. To summarize this still-unfolding artwork is not just impossible; it contradicts everything I know to be true. The more I encounter Vinge/Müller’s work, the more unmanageable, contradictory, and irreducible I believe it to be. The Saga exceeds the limits of comprehension and embraces the impossibility of ending. Sometimes, the audience leaves, and the performers continue; sometimes, the technicians leave, and the audience and performers carry on; sometimes, the shows are canceled, shut down, or abandoned until the next night. In each instance, the Saga refuses to conclude because its commitment to the image is unending. And it is unending for me too. I never leave their performances, even when I am bored, even when I am tired, even when my body and brain cannot absorb any more of their art. Because to know it, I must commit to it.

Since I saw their Wild Duck fifteen years ago, I have fought against the Saga’s expansiveness. When I look at my notebooks from performances I watched, each turn of the page and passing hour of the production, my descriptions become more fragmented, dream-like, single words written in a looping, sleepy script. On those pages I see how the shows wore me down, ground my senses into submission, and freed me from reality. My experience with Vinge/Müller’s work is that of being outlasted. I hang in there, but only by a thread, and each glimpse of comprehension flickers out in the next moment. My resolve is weakened, but my perception is more open. When I attend a subsequent performance to remember what I saw, the scenes are reconfigured into something new. My notebooks document two of the Ibsen-Saga’s great pleasures: trying to piece it together and then submitting to an imagination and a commitment far greater than my own.

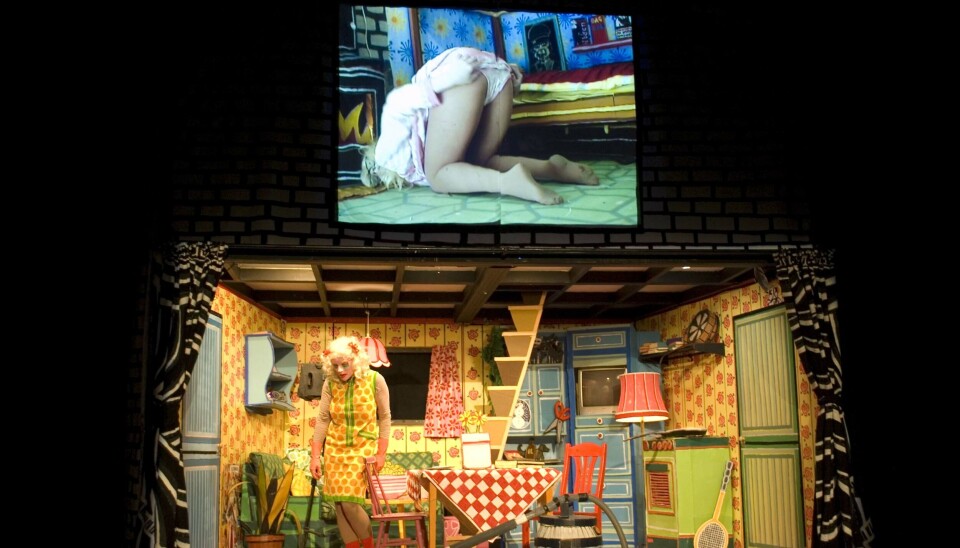

DESPITE CONJURING THE INEXPRESSIBLE, few theater projects have been more fixated on the idea of totality. After all, Vinge/Müller’s goal is not only to stage all of Ibsen’s plays but to uncover and materialize all their connections and all their images across time and map them into a totalizing fiction that weaves Ibsen’s themes into a massive tapestry. Their visual language is one of totality; a total scenography: not a set or an installation, not costumes or masks, or props, but a world, a universe of their imagination: every inch coated in paint, every voice distorted, every face a mask, every action underscored with their composer Trond Reinholdtsen’s sonic brushstrokes. A commitment to the impossible dream of art: to bring a new world into existence.

I will try to explain what I mean by the image as commitment in a small scene from Vegard and Ida’s John Gabriel Borkman. This was before they had been invited to Theatertreffen, before their artworks and intentions became fodder for newspapers. Here, there was a very simple scene: Vegard appears on the empty black stage and begins to paint the floor white with a long-handled roller brush. Over the next ten minutes, the stage is transformed from black to white. As soon as this task is done, an actor in a wolf mask appears from the trap in the middle of the stage and flings a shovel full of dirt across the wet paint. The wolf continues shoveling until the black stage turned white is covered with fresh soil.

Whether or not you know the significance of the wolf to the play, you will know the work that occurred, the time it took to complete, and the effort of creating a world so that it can be replaced by another. No critic has written about this scene, no one will be scandalized or awed by its beauty, but for me, it holds everything. The effort. The futility. The joy. The transformation. The world remade and unmade in the same breath. That’s the language of commitment. That’s what I love.

Because when I witness that dedication, that patience, that belief in the power of the image—I feel brave. I feel my world get bigger. My imagination grows. My love deepens. My will to commit myself to the things and people I care about—gets stronger. I feel free. That’s what Ibsen wanted. What his protagonists wanted. That’s what the art I love wants: To get free. By going deeper. By making a world. By building a temple. That’s what Vinge and Müller’s art gives me: a temple where I’m free to commit myself to art.

This kind of art is rare. But it exists. It is here, in this room, in this project, in this temple of images, and for that, I am grateful.

Thank you.