FEAR and the far-right in Germany

I want to talk a little bit about my experiences with right-wing extremist groups in Germany. I am a writer and director. I work in Germany, but also in other

European countries. In 2015 I created a show at the Schaubühne in Berlin, which is a state financed theatre and one of the fairly big theatres in Germany. I was creating a show called Fear, and as you know, in 2015 Germany accepted quite a number of refugees from Syria and other countries and gave them refuge. At first this was actually an amazing historical step, because most Germans were very welcoming and helpful and created a very friendly environment for these refugees. And then, soon after, there was a sort of backlash created by the right-wing forces in the country, and they were working with fear and anxiety as political tools to scare people.

They created narratives you all know – that Europeans will soon be outnumbered by Muslims on their home continent, that Europe will no longer be a Christian, European continent anymore, but rather a continent run by Muslims, and there were also some grotesque narratives; in ten years we will not be allowed to celebrate Christmas anymore, etc. They were basically creating this kind of fearmongering narrative about how Europe would very soon be taken over by these refugees.

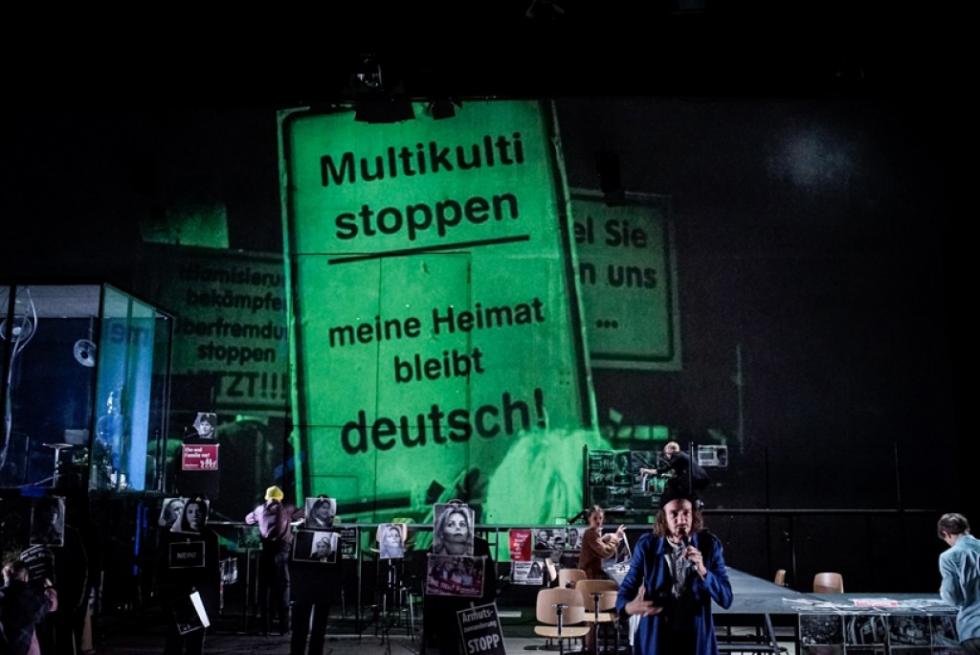

I was making a show about our society, the German and European society at the time, and I was interested in the way that radical right-wing groups argued, the rhetoric they were using, what propaganda they were using, what language, what memes on the internet, and how they are connected with each other. There are actually a lot of connections between all these small groups, and they are much better connected than the democratic groups and organisations in our society.

The show was not only talking about right-wing politicians and their language and strategies – it was taking about different groups of society, it was talking about a diverse society confronted with challenges and how different people reacted to that. It was also about the middle class’ fear of losing wealth, and the fear of a young generation becoming part of a precariat workforce. It was dealing with fear on a lot of levels, also with anxiety on a very personal and intimate level, but I would say this show was highjacked by right-wing activist groups that used it to push forward their agenda.

In the show I was talking about activists from the far right in a critical way using satire and humour. I was also naming them. I was using video images to show some of the main politicians of that political formation. I was basically doing a sort of Google research on stage, where you could see the slogans that the far right politicians were using on their posters and on the internet, but you also saw their faces. I was showing quotations by politicians of the far right that were homophobic, racist and antisemitic. Often these politicians used the same language as the original Nazis had used in the 30s and 40s. So there is a strong relationship between this use of language and the use of a political strategy that we had already experienced in Germany in the first half of the twentieth century.

After the premiere I was extensively attacked by the AfD, Alternative für Deutschland, which consists of a wild mix of right-wing people; some are extreme ex-Nazis, while some are more pending towards the Conservative Party. Some of them are really radical and some are more in alliance with the Christian Democratic Party, or used to be members of the Christian Democratic Party that decided to move further right.

One of the main AfD-politicians, Beatrix von Storch,who happens to be the granddaughter of Hitler’s finance minister, created a false narrative after the opening night. She claimed that her car was burned by a ravaging group of people that had attended the premiere of the play, and that the play was inciting hate on such a level that the audience at Schaubühne went out into the streets of Berlin, looked for her car, and burned it. That is of course ridiculous. As anyone of you know, the Schaubühne is a very prestigious and I would say bourgeois theatre. The audience usually drink some champagne or chardonnay afterwards, they debate and discuss, and then, I don’t know, they have dinner at an Italian restaurant. And how would anyone know where to find the car of that politician in a city of 4 million inhabitants like Berlin. It turned out later that the car was burnt but not close to the premiere of my show and of course there was never ever evidence that the Schaubühen audience had anything to do with it. Yet, the false narrative was repeated on the internet by the right wing party over and over again. So this false narrative was very successful in social media and also in parts of the German media that is more right-leaning or right-wing.

I’ll give you a list of what actually happened in the course of that. Immediately two days after the opening night there was an online petition calling people to sign against me and against my work, and basically against financing my work. You could sign so that the government would not give money to my projects anymore. The strategy of the far right is to attack individual artist because they are most vulnerable. They create false narratives and they pick out the most vulnerable person in the whole system, which is the actual creating artist who is often not backed up by the media or even by the theatre system. And they use the vulnerable spot: Create hatred against that individual and stir up an internet mob that violently demands to cut all funding of that artist and thus to destroy the career of that individual artist.

My show Fear was widely discussed and debated, there were reviews that were positive and reviews that were negative, but they were mostly still within the realm of art criticism. But what the right-wing extremists did was attack me personally. I got death threats by email, there were numerous calls to the theatre where people were threatening random theatre employees, telling them they would burn their cars. We had Nazi-graffiti in front of the box office. We had people from right-wing parties trying to disrupt the performance, filming the actors with their mobile phones or even with a camera while they were performing. There were a lot of hateful articles written on different online blogs and far-right websites. They also did something that Donald Trump always did – giving derogatory names to people he disliked – so in all these blogs I was always called «the talentless Falk Richter». They would always put the word «talentless» in front of my name.

This is also a way to discourage artists to speak out by intimidating them. At the time I was releasing a new book of mine and going on a reading tour, and because of the death threats I was receiving at the time I had police with me, I had guards that were protecting me during those readings. And that was such a change in my life; I was living in a free and democratic country and all of a sudden, I had to be protected from right-wing extremists that actually sent me emails saying they wanted to kill me. This of course has an effect on other artists as well, and it has an effect on other theatres, because it intimidates them. Some people might think twice before speaking out politically, before speaking out openly, or they might think «Hmm, should we program a play by Falk Richter in our theatre? Should we stage his work? Because it will probably get us into a lot of trouble, so maybe we should just have another writer instead?»

I have to say, it was a heavy time for me, but I got a lot of support as well. In Germany we also have what we call the Deutsche Kulturrat, and they were actually releasing a statement at the time totally backing up my artistic choices, saying «we do have freedom of the arts and freedom of speech in Germany, and Falk Richter needs to be protected and he needs to be able to do his work.»

There were also a lot of newspapers backing me up, even if they were criticising the work or saying «maybe we don’t like his style or maybe we don’t like his aesthetics, but we do back up the fact that he’s an independent artist, and he has all the rights to create a piece of work in which he expresses his opinion.» And what was also very important was that the theatre and the artistic director Thomas Ostermeier were backing me up.

What also happened over the course of these events was that politicians from the AfD were taking my performance to court, so I had four court cases against me, which I won. I think that’s important – they kept going to court, but they kept losing. However, each time they went to court against me they raised a lot of hate against me and against the theatre in their right wing community, so new hate storms were incited on the internet and a number of articles filled with false accusations and false descriptions of my play were released on right wing internet forums which each time resulted into yet another wave of hate mails that I and the theatre received. Each time we were heading towards a new court case, the whole thing started again.

I got used to it after a while, but it’s a very critical situation because as I said before, a lot of young artists or artists who are not so established as I am would be afraid that something like this might ruin their career or that they would not be granted money anymore or – even worse – that they would really be attacked physically. So I think it is very important that the art community and also the politicians understand that this is a bigger issue than just a piece of theatre or a piece of art being outrageous or not nice or «too radical» or whatever – this is actually about protecting our freedom of art and our freedom of speech.

The way I see it, the goal of the far-right is achieving a political situation similar to the situation in countries like Hungary, Poland, Russia, or the US under Trump or Brazil under Bolsonaro; basically, their goal is the disruption of democracy, and the final goal is white supremacy and a nationalistic totalitarian patriarchic society, and on the way it’s the end of any kind of criticism by artists. The AfD have actually made statements about their idea of theatre and what art and theatre should deliver in their eyes, and I’m paraphrasing them now: «Art shall be nationalistic and heroic. It must create positive feelings for the audience towards our nation, and the art has to be done in a way so that it values the history of the nation.»

With regard to Germany this is quite problematic, because you cannot value our history without playing down the Holocaust or playing down the Nazi regime. You cannot talk about German history without being critical and acknowledging the fact that some of the worst crimes against humanity have been committed by Germans in the name of «the superior arian race», but that’s exactly the agenda of the far-right in Germany – to downplay the atrocities of our history in order to reintroduce a political system and political propaganda similar to what we had in the 30s and 40s of the last century.

Basically, the idea is a nationalistic right-wing religious patriarchal system, where people from the LGBT-community shall not be visible in society, so art should not deal with any queer issues. Women should stay at home and have at least three children, otherwise they are not considered to be real women. Artists shall create nationalistic historic art that celebrates the current regime and the glorious historic successes of the nation. Germans are usually just considered Germans when they are white, or you could use the word Aryan, which of course is not used by the far-right at the moment, but basically that is what it comes down to. So all the Germans who live in this country that are not white or whose parents or grandparents came here from other countries are not considered German by the far-right.

This is an ideology that talks about bloodlines again, and there you see a direct connection to Anders Behring Breivik for example, who actually believed in similar white supremacist ideas. The enemy of the far-right is clear: It’s the critical left, the liberal press, it’s feminists and queer activists, it’s non-white people and non-Christians and it’s the freedom of those artists who are critical or experimental in their art, that are wild in their form maybe, who push the boundaries of a bourgeois society, artists who have a critical approach towards the government, the church, the concept of nation, the concept of a heroic history, or heteronormativity, or who are criticizing white supremacy, racism, homophobia and a patriarchic system.

What we learned in the course of all these events was that discussions and talks with people from the far-right never turned out to be constructive or never helped building brigdes of understanding each other. There was this very naïve idea at the beginning that we could create roundtables and invite people from the far right that had attacked us to talk to us and with us about art, about what we’re doing, and that we could explain our art to them, explain how satire works, how humour works on stage, that the arts and the theatre have the right to be critical towards political parties and agenda but it never worked out.

Basically, the far-right only used these platforms to spread false narratives and to insult the participants of the talks on a very personal level. Often these discussions collapsed because the far-right representatives were just constantly trying to trigger and insult the other participants, and they used the platform to spread racist, homophobic, anti-Muslim and antisemitic narratives and lies, so it was very difficult to try to uphold any kind of constructive and meaningful debate. There were so many false narratives and lies in the discussion it would often take too long to fact-check them all the time, so it was almost impossible to keep our discussions running. The far right don’t play fair in the discussions or in the way they attack the artists, so the discussions with the German far-right never got you anywhere but to a place where they spat out offensive insults, tried to avoid answering questions, derailed the conversation with whataboutism.

In the end we decided we would have to exclude members of the far-right from these discussions, but the discussions continued. You just heard my colleagues who in the end founded the group Die Vielen, which was not around when I was attacked for my play Fear, but which I think founding this collective was an amazing and very important step because it made clear that the majority of the German society is in fact in favour of freedom of speech, in favour of freedom of the arts, and in favour of democracy and in favour of a diverse, pluralistic, open society. The majority of Germans are not racist, not antisemitic, and not anti-gay. We do actually have a soliddemocratic society, but we also have to protect that society against the far-right.

Since my play Fear, the AfD has attacked many theatre productions. The strategy is always similar; creating false narratives, attacking the artists on a personal level, claiming the artist is not worthy of getting money for their work, claiming the artist is not an artist – that’s also a trick they always use, saying this is not art, this is basically degenerated art». They are using this term «degenerated», it’s basically stemming from the Nazi term «Entartete Kunst».

They’re always calling for the defunding of certain artists, and they create a certain narrative on their platforms of the decent, ordinary, hardworking people on the one hand, and the decadent, degenerated artists on the other hand who get money for their degenerated, disgusting work, which is taken from the poor man’s pocket who then does not get proper health care or a proper school system because all the money goes to the decadent artists who do their useless and degenerated art with it. We all know that this is not true. This is not how the distribution of money works in our societies and the amount given to the arts is relatively low even in the rich countries. But this narrative helps dividing society and it stirs hatred against unwanted critical artists. And it helps manifesting the narrative of the far right that they will save the honest simple working man from the degenerated crazy decadent artists and their useless art.

I would want to close by saying that I find it important to understand that the freedom of the arts is a very important value in our democratic society. Art needs to be free, art needs to have a safe space, and the safe space needs to be protected by society and also by the government, and by all institutions, because the freedom of art is guaranteed by our democratic constitutions, but not always enforced – often the artists are left on their own when they get attacked by the far right.

And I also want to say that art – and that’s the tricky thing, where a lot of conservatives get confused – does not have to be nice and friendly and pleasing. Art can be disturbing, it can challenge your own values, it can sometimes be crude and maybe radical, it can be excessive, it can be anti-bourgeois, but still art needs to be free. If we don’t have free art in our society, it’s not a democratic society. Then we have a sort of totalitarian society that tells the artist what to do. (Published April 9th 2021).